Correlation Isn't Causation, But It Makes Profitable Clickbait

Tylenol and autism, diet soda and depression, pesticides as bad as smoking: sloppy observational epidemiology drives panic and ignores biology, chemistry, and toxicology.

This newsletter is free, but consider supporting a biomedical scientist trying to combat the war on health by upgrading to a paid subscription:

Every week, the headlines blare a new health apocalypse: “Diet soda causes depression!” “Tylenol in pregnancy linked to autism!” “Pesticides are as bad as smoking!”

Except…NO—they don’t. What they have in common is one of the most abused terms in science: “association.”

An association (or correlation) means two things show up together in the same dataset. It does not mean one causes the other. Sometimes there’s a real link, but most of the time, especially in weak observational studies, it’s coincidence, confounding, or statistical noise.

Ice cream sales and shark attacks follow the same trendline. Both rise in the summer. Are people getting attacked by sharks because they ate Häagen-Dazs? Of course not. Both are driven by weather and summer activities. Correlation does not equal causation. Correlation can hint at a pattern worth studying, but it’s not proof.

And yet, when it comes to health, that logic gets tossed out the window. You don’t see headlines every summer screaming “Ice Cream Kills!”

But that’s what’s happening with poor-quality epidemiology papers churning out these kinds of claims, which get laundered by university PR, picked up by media outlets, and weaponized by wellness influencers. If we know ice cream doesn’t cause shark attacks, why do we fall for “diet soda causes depression”?

Some Recent Offenders: Observation Spun as Causation

Tylenol during pregnancy isn’t causing autism

The Tylenol–autism claim has no causal data. The most robust studies show no relationship. The weaker ones that do?

They’re examples of confounding by indication.

Pregnant people take acetaminophen for fevers, infections, or pain—all conditions which are themselves linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes, including autism. In fact, maternal fever and infection consistently show an association with autism, though it’s much weaker than the overwhelmingly strong genetic contribution to ASD.

That’s why every major scientific and medical body continues to recommend acetaminophen as the safest pain reliever and fever reducer during pregnancy. Untreated fever and pain are far greater risks.

But by the logic of Baccarelli, RFK Jr., and the Trump Administration, we could also conclude that organic food causes autism. The data are clear: the more organic food people buy, the more autism diagnoses there are!

Sarcasm, yes—but it illustrates the absurdity of spinning correlation into causation.

This tactic is particularly prevalent when it comes to false claims about causes of autism, including vaccines. (for one example, read the article below):

As an aside: I wrote about the seedier underbelly of this topic here: how junk science published by academic researchers fuels a cycle of exaggerated claims to lend unearned credibility to dangerous misinformation.

In today’s era of clickbait and chemophobia, this tactic is everywhere. Why? Because crude “population-level” analyses are quick, cheap, and can be done by people with no real expertise in the biology of the condition they’re “studying.”

Remember: epidemiology is data science, not biomedical science. Training emphasizes math and statistics, not cancer biology, biochemistry, toxicology. So you end up with papers reporting on patterns about complex health conditions authored by people who don’t understand the science driving them. That’s why epidemiologists should be working with the scientific experts on these topics, not cosplaying as biomedical scientists.

Pesticides are NOT the new Marlboros

Remember headlines last year? “Pesticide use is on par with smoking for cancer risk.” The claim came from a Frontiers in Cancer Control and Society paper so bad it should never have made it past peer-review.

The authors lumped together county-level data on 69 USDA-monitored pesticides (ignoring dozens used in organic farming since they aren’t monitored by the USDA) and treated them as a single chemical “exposure.”

This is anti-science nonsense.

You cannot ignore basic principles of chemistry, toxicology, and biology. Herbicides act on plants, fungicides on fungi, insecticides on insects. Different targets, different toxicology, different biology. What impacts a plant doesn’t automatically impact a human—plant cells are dramatically different than mammalian cells. Same for insect cells and fungal cells.

Adding them up and declaring a “cumulative cancer risk” is like adding apples, oranges, and pineapples and calling them all bananas. This alone should have gotten this paper rejected, but it gets better.

When they looked by cancer type to try to find a link between reported cancer cases and pesticide use, there was no consistent pattern (because there isn’t one).

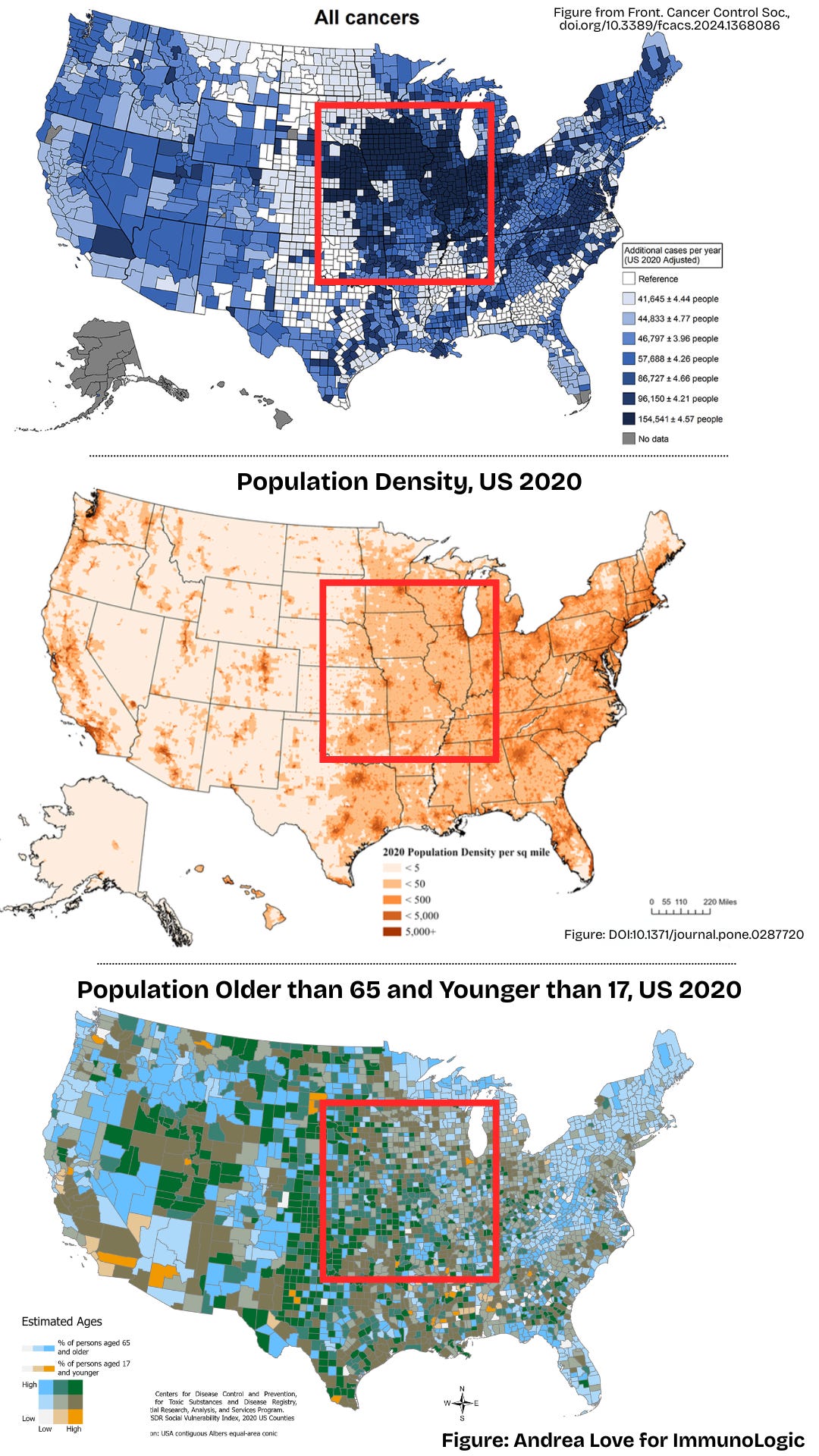

So to create the conclusion they wanted, what did they do? They pooled all cancer cases, skipped normalizing for population size, and created a map of “excess cancers” they think are because of pesticide use. Not surprisingly, the map lit up in the Midwest and Florida—places with large agriculture regions. Their conclusion? More farms, more pesticides, more cancer. Correlation equals causation. Done.

Except they didn’t control for the obvious:

Cancer type: cancers are hundreds of diseases with many different risk factors and causes. HPV causes nearly all throat, cervical, anal, penile, vaginal, and vulvar cancers. Hepatitis B virus drives 60% of liver cancers. Inherited gene mutations, like BRCA and Lynch syndromes account for others. These weren’t included either, obviously. You can’t add them all up and call it a day.

Age: the biggest driver of cancer risk. 88% of cancers occur over age 50, 59% over the age of 65. Median age of cancer diagnosis is 67. The counties they flagged? Many have more than 30% of the population older than 65. Not a single correction—or mention—of age.

Population density. More people = more raw cases.

If a county of 100,000 has 2,000 excess cancer cases, that’s 2%. If a county of 10 million has 100,000 cancers? That’s 1%—half the rate. But because the authors present raw numbers on their map, the latter looks “worse” on a heatmap.

You can’t present raw numbers when trying to making a population-level claim: that’s wildly misleading and statistically wrong.

Known modifiable risk factors. The top modifiable risk factors for cancer include, smoking, alcohol consumption, sedentary lifestyle/obesity, low fiber intake, UV radiation exposure, and age. They adjusted for smoking, and that’s it.

Socioeconomic and healthcare factors: healthcare access, screening rates, income, and urban vs rural populations. All ignored.

This is textbook ecological fallacy: taking population-level associations and pretending they apply to individuals.

Yet, because everyone loves a synthetic chemical villain, headlines went wild with this paper for weeks — and fueled anti-farming rhetoric and policies that will reduce farmers’ ability to grow food for you.

The reality:

75% of liver cancers are caused by hepatitis viruses, smoking, and excess alcohol consumption

86% of lung cancers are caused by smoking

63% of throat cancers are caused by HPV infection

15% of colorectal cancers are due to inadequate fiber intake

Pesticides? Zero proven cancer deaths under real-world exposures.

If pesticides were really “as bad as smoking,” America’s farmers would be the sickest population in the country. They aren’t.

Ultra-Processed Foods aren’t killing everyone

A BMJ umbrella review last year declared eating “ultra-processed foods” (UPFs) is associated with…basically everything bad: mortality, depression, diabetes, cancer.

Terrifying, right? Good thing it is false.

This is correlation by overgeneralization.

These giant reviews lump observational data together but rarely correct for the real drivers of poor health between people who report eating UPF versus those who don’t:

Income level and socioeconomic status

Overall diet quality

Food desert proximity

Smoking and alcohol intake

Sedentary lifestyle and activity level

Obesity and other comorbidities

If these could be adequately corrected for in these types of data dredges, you’d lose the “association” between UPFs and adverse health effects.

Data vilifying UPFs fail to show any direct connection between a specific food or food ingredient. Rather, it is the overall dietary pattern: where people who report eating UPFs are consuming less fiber, lean protein, and other important nutrients.

But of course, the headlines don’t say that, right? They say “chemical in ultra-processed foods are causing cancer, mental illness, cardiovascular disease, death!” all claims which are wholly unsupported by broad overgeneralized observational analyses.

I actually called out this review and resulting media clickbait last March:

And what even counts as a UPF? There’s no standard definition; under the NOVA system, a Twinkie and a nutritionally dense MRE both qualify as “ultra-processed.”

By this logic, foods critical for soldiers, disaster victims, or people in food deserts also cause cancer, mental illness, heart disease, right?

90% of Americans don’t eat enough fiber, a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disorders, type 2 diabetes, and several cancers.

Nuance doesn’t sell ads. So headlines scream “chemicals in UPFs cause cancer” while ignoring the real issue: people reporting high UPF intake also eat fewer fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and fiber. But it’s easier to scare people about “chemicals” than to encourage eating more whole grains and legumes, right?

Diet soda isn’t causing depression, either

A recent paper in JAMA Psychiatry claimed diet soda causes depression, supposedly due to changes in a single genus of gut bacteria—Eggerthella.

The study can’t make that claim: it was an observational study based on self-reported soda consumption with some weak fecal molecular biology analysis tacked on. Their conclusions are speculative at best, and unsupported by data they present.

Those buzzwords—“gut health” and “microbiome”—are almost always red flags when used outside serious microbiology research. As a microbiologist, I cringe at how often they’re used to attribute causation where none exists, and as we see here, not just in wellness industry marketing ploys.

Yes, the microbiome matters—it’s trillions of bacteria, viruses, and fungi living in and on us are crucial for immune system function, nutrient metabolism, cardiovascular and GI health, and more. But it’s way too complex and self-regulating that a single food would completely disrupt its function. Honestly, these types of claims are actually insulting to human biology.

This is why these studies bum me out. We have learned many things about the microbiome over the past few decades. But instead of investing in rigorous, mechanistic research, the field is drowning in poorly done observational studies churning out claims, trying to link a “change” in microbiome to some health outcome.

The authors don’t even show Eggerthella levels are meaningfully changing, let alone that the change has a health impact. It just shows that people with diagnosed major depressive disorder (MDD) report drinking more soda than those not diagnosed.

That’s correlation, not causation.

That could just as easily be reverse causation: depression alters eating and drinking patterns.

The relative risk difference they report is about 8%, which could be entirely due to small sample size and confounders. In fact, their MDD group had higher BMI values, meaning comorbidities like obesity could be driving the pattern. None of this is corrected for adequately.

Diet soda isn’t destroying your microbiome and making you depressed.

This study shows how observational data gets oversold. It doesn’t prove causation in either direction—or even that soda and depression are related in any meaningful way.

And yet, headlines proclaim otherwise, because blaming diet soda for damaging your “gut bacteria” is profitable clickbait, even if it’s wildly misleading and erodes trust in science.

Seagulls Don’t Break Railings and Tylenol Doesn’t Cause Autism

Weak observational studies have become currency in today’s broken publishing landscape and are fuel for academic PR teams, media outlets chasing clicks, and wellness influencers chasing profit.

But correlation is not causation. It’s a starting point, not a finish line.

And yet every day, another weak “association” gets spun into a definitive “X causes cancer” or “Y wrecks your microbiome.” The result? We waste money on bad science, waste time debunking recycled pseudoscience, and distract from the real, evidence-based drivers of health: infectious diseases, social determinants of health, healthcare inequities, legitimate lifestyle factors, and age.

Those may not be as flashy as demonizing soda, pesticides, or “chemicals,” but they’re the reality. Until we stop treating flimsy correlations like fact, we are going to keep wasting energy on false claims while actual risks keep harming our society.

We all must join in the fight for science.

Thank you for supporting evidence-based science communication. With outbreaks of preventable diseases, refusal of evidence-based medical interventions, propagation of pseudoscience by prominent public “personalities”, it’s needed now more than ever.

Stay skeptical,

Andrea

“ImmunoLogic” is written by Dr. Andrea Love, PhD - immunologist and microbiologist. She works full-time in life sciences biotech and has had a lifelong passion for closing the science literacy gap and combating pseudoscience and health misinformation as far back as her childhood. This newsletter and her science communication on her social media pages are born from that passion. Follow on Instagram, Threads, Twitter, and Facebook, or support the newsletter by subscribing below:

As always, I am so grateful for your clear, data-driven approach. I am stunned by the impact that pseudoscience is having upon our culture. Nearly every day, I read social media posts about junk science, posted by intelligent, well-meaning people. I attempt to gently debunk at least the most spurious claims, based on what I’ve learned from reputable scientists. It’s a long road….

This is mostly drawn from observational data over my 35-year career as a psychotherapist, but I can claim, with very few exceptions, that depression DOES alter the eating patterns and activity levels of people who are afflicted. Claiming that what they consume causes depression certainly doesn’t show up in my professional journals. It seems to be utter nonsense, and implies that people with depression are somehow responsible for bringing this upon themselves. That’s cruel.

Great piece by Dr. Love. This lesson that correlation is not causation needs to be taught more effectively at all levels of education. It is a classic logical fallacy, often phrased in Latin as cum hoc ergo propter hoc (“with this, therefore because of this”). Correlation can be a starting point for investigation but it is never proof of causation. When observational studies are stripped of nuance, misreported by media, and weaponized by bad actors, they mislead the public, erode trust in science, and distract from the real drivers of disease such as genetics, infections, lifestyle, and social determinants.