Fear-mongering about "processed foods" is harming public health and science literacy.

The extent of processing of a food is not directly related to nutritional content

Yes, the media outlets are at it again, misleading and demonizing foods.

Posts from all news outlets are making unsubstantiated claims about processed foods and ultra processed foods which are not representative of the actual data.

No one is telling anyone to have a diet solely consisting of ice cream and potato chips. The problem is, these types of fear-based messages are exploiting the risk perception gap, which I discussed previously.

These media outlets are doing a poor summary of a recent meta-analysis published in the British Medical Journal. The analysis looked at association of UPF (in this instance, they adhere to NOVA classification, more on that below) and a variety of health outcomes. NONE of the data demonstrate a causal relationship - meaning these are merely associations. Before we get into that, let’s discuss the concept of food and processing and what it actually means.

We need to do away with the notion that foods are inherently good or bad.

Foods are fuel for our body. Some foods are more nutrient dense and should be a larger proportion of our diet as they contain, in addition to calories from macronutrients, other micronutrients that aid in our physiological processes. But demonizing specific foods, or worse, specific classes of foods, is elitist and harmful.

Virtually all foods available for purchase are processed to some degree, even fresh produce. Food begins to deteriorate and lose nutrients as soon as it is harvested, so even the whole fruit sold in the produce aisle undergoes several processing steps before being sold. Terms surrounding processed foods are not consistently defined and have different meanings to different people.

Processed and ultra-processed foods are NOT inherently “unhealthy” and this messaging is creating fear and health anxiety.

Technically, everything we eat is processed to some degree, even fresh produce.

There is no standard definition for what makes a food processed. In pop culture, the term has been used as a cudgel to insinuate certain foods are ‘toxic’ or ‘bad’ compared to others. Yes, even fresh produce is processed before it gets to the grocery store. These are some of the major food processing steps that occur before even “whole foods” get to you:

Cleaning and Sorting: This is the first step in food processing, where raw materials are cleaned to remove dirt, stones, contaminating microorganisms, and other impurities. Sorting involves separating the food by size, weight, or quality.

Grading: Foods, particularly fruits, vegetables, and grains, are graded based on quality standards. This affects their market value and suitability for different types of processing.

Peeling/Skinning: Many foods, like fruits, vegetables, and certain meats, undergo peeling or skinning. This can be done mechanically or chemically, depending on the food type.

Cutting/Chopping/Slicing: Foods are cut into uniform sizes to ensure even cooking or processing. This is common in vegetables, fruits, meats, and fish.

Blanching: This is a process of boiling or steaming food briefly and then plunging it into cold water. It's used to soften food, to brighten its color, and to reduce bacteria.

Pasteurization/Sterilization: This involves heating food to a specific temperature to destroy microorganisms. It's commonly used for milk, juices, canned foods, and others.

Fermentation: Many foods like yogurt, cheese, beer, and bread undergo fermentation, where microorganisms like yeast or bacteria convert organic compounds into alcohol or acids, adding flavors and aiding preservation.

Drying/Dehydration: Removing moisture from food prevents the growth of microorganisms and prolongs shelf life. This method is used for fruits, vegetables, meats, and fish.

Freezing: Freezing food slows down decomposition by turning residual moisture into ice, inhibiting the growth of most bacterial species. It's widely used for meats, vegetables, fruits, and prepared meals.

Canning: Food is sealed in airtight containers and then heated to kill bacteria. This method is used for a variety of foods, including fruits, vegetables, meats, and seafood.

Smoking: A process used mainly for fish and meat, smoking imparts flavor and aids in preservation.

Pickling: Foods are soaked in solutions like vinegar or brine to extend shelf life and add flavor.

Milling/Grinding: Grains are milled to produce flour, while nuts and seeds can be ground into pastes and butters.

Extraction: This involves extracting oils or juices from foods, such as in olive oil production or orange juice extraction.

Emulsifying: This process is used to mix two liquids that normally don't mix well, like in the making of mayonnaise or salad dressings.

Fortification/Enrichment: Adding vitamins and minerals to foods to enhance their nutritional value.

Packaging: Finally, foods are packaged to protect them from physical, chemical, and environmental factors. Packaging also includes labeling with information about the product.

Each of these processes can vary greatly depending on the specific food item and the desired end product. There are specialized processes for specific foods beyond this.

But when you ask members of the public, the phrase ‘processed food' means different things:

Canned or frozen foods

Foods with preservatives (salt and sugar are preservatives, fyi)

Foods with ‘unnatural’ or ‘added’ ingredients

General properties of processed foods according to public understanding include:

Any steps taken to lengthen the shelf-life of a food (even freezing whole fruits or vegetables)

Canning, freezing, drying, or otherwise storing for longevity

Addition of some oils, sweeteners, and preservatives

The primary ingredient is still the whole food

Not all processed foods are low in nutrients, and processed foods are not inherently harmful. Less nutrient-dense foods are not a replacement for more nutrient-dense foods, but they’re still fine to consume in moderation.

There is not a direct relationship between whether a food is processed and its nutritional content.

Processing has a complex influence on nutritional content of food. Processing can result in both positive or negative consequences, depending on the technical process applied and the food in question. From a scientific perspective, the relationship between food processing and nutritional value are not linear. We need to dissociate these concepts.

There is no standardized definition of what a processed food is.

A study published in Trends in Food Science and Technology reviewed over 100 scientific papers to assess similarities in classification for processed foods. They found that most criteria are not aligned with existing scientific evidence on nutrition and food processing.

Other key findings related to classification of processed food:

There is no consensus on what determines the level of food processing even among scientific agencies

Classification includes the extent, nature of change, place, and purpose of processing

Processed food concepts relate to naturalness, additives, convenience, home cooking

Food classifications embody social and cultural elements and subjective terms.

“’Processing’ is a chaotic concept and while it should only be concerned with technical processing methods, it is not. Most classification systems do not include quantitative measures but, instead, imply a correlation between ‘processing’ and nutrition.” This is further complicated by ongoing discussions about the concept of “whole food” in relation to “healthy diets” and the risk assessment of food additives which is quite nuanced.

While low nutrient density processed foods should not make up the majority of our diet, even those are not inherently dangerous and can be consumed in moderation. It’s also important to consider the accessibility of these foods which are often more affordable and have a longer shelf-life. Many processed foods are nutritious (e.g. frozen fruits, yogurts) and often are more accessible for people who lack access to fresh foods, especially those of lower socioeconomic status.

Even worse, the phrase ultra-processed food (UPF) is frequently thrown around by media outlets and wellness influencers. They make an array of claims about eating UPFs, from depression to cancer. It sounds scary, right? But this is not the reality.

There is no standardized definition of what qualifies as an ultra-processed food (UPF)

The term "ultra-processed food" (UPF) is a nebulous term with no standard definition. This is exploited and used to fear-monger by media outlets and influencers on social media.

No standardized definition: Different researchers and institutions define ultra-processed foods in slightly different ways. While most agree that these foods are significantly altered from their original state through processing, the specifics of what constitutes "significant alteration" can vary.

NOVA Classification: The most commonly used framework for defining UPFs is the NOVA classification, which categorizes foods into four groups based on the extent and purpose of their processing. However, even within this framework, there is ambiguity for certain foods.

Ingredients Criteria: Some definitions focus on the number and types of ingredients, especially added ingredients like preservatives, colorings, artificial flavors, and emulsifiers. Yet, there's no universally agreed-upon threshold for the number or types of additives that would classify a food as ultra-processed. Many people also conflate added ingredients with ‘artificial’ (you knew the appeal to nature fallacy would appear here), but plenty of added ingredients are natural substances, added to help extend shelf life (salt and sugar are preservatives, remember).

Cultural and Regional Differences: Food processing techniques and dietary habits vary greatly across different cultures and regions. This diversity makes it challenging to apply a uniform standard worldwide for what constitutes an ultra-processed food.

Industrial and Homemade Foods: There's a lack of clarity in differentiating between industrially processed foods and those that are processed at home or in small-scale settings. This distinction is crucial because the same food item could be classified differently based on where and how it is processed.

Evolving Food Technologies: Advances in food technology continually change how foods are processed, which can lead to new products that don't fit neatly into existing categories of food processing.

While most people acknowledge the ‘concept’ of ultra-processed foods is widely recognized, there's a lack of consensus on the definition and criteria for categorization. This lack of standardization can lead to challenges in research, dietary guidelines, and public health recommendations.

What about the difference between processed and ultra-processed foods?

Again, there is no standard definition. The main difference, according to public perception (not science) is the extent to which they have been processed and the number of ingredients they contain. Processed foods are minimally processed to improve taste, texture, or shelf life. They may contain added ingredients (e.g., salt, sugar, oil), but they retain most of their original nutrients.

Examples include canned veggies, frozen fruits, bread, cheese, and yogurt.

Ultra-processed foods have been heavily processed and contain many added ingredients. They often have a long shelf life and are designed to be tasty. Examples include candy, soda, and packaged meals. They’re typically considered to lower in nutrients and higher in calories, sugar, fat, and sodium.

UPFs are generally viewed as being designed around affordability, convenience, and tasting “good,” often at the expense of nutrients (especially compared to caloric content). UPFs can have reduced fiber, protein, vitamins, or minerals relative to calories, but that is not a requirement or a standardized phenomenon.

But processed and ultra-processed foods are not inherently unhealthy or dangerous if they are consumed in moderation. It’s important to consider the accessibility of these foods which are often more affordable and have a longer shelf-life. Many processed foods are nutritious (e.g. frozen fruits) and often are more accessible options for people who lack access to fresh foods.

But I heard that UPFs cause all sorts of negative health outcomes, like obesity, cancer, diabetes, depression, and more.

While UPF are a hot topic of study and discussion, the vast majority of data in humans currently are observational and epidemiological data that show ASSOCIATION, not CAUSATION. Unfortunately, many of these claims have been taken out of context and used to spread unfounded fears about food. The discussion around UPFs often centers on their health impacts, with many studies linking them to negative health outcomes. However, the lack of a standardized definition means that research findings can be inconsistent and not always directly comparable.

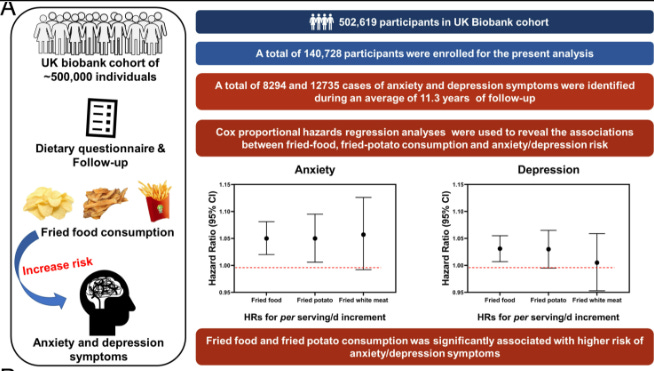

Remember that headline about French fries and depression that was circulated wildly? Nearly every news outlet picked it up.

“The new claim comes from an April study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, which looked at the correlation between fried food consumption and the risk of anxiety and depression.”

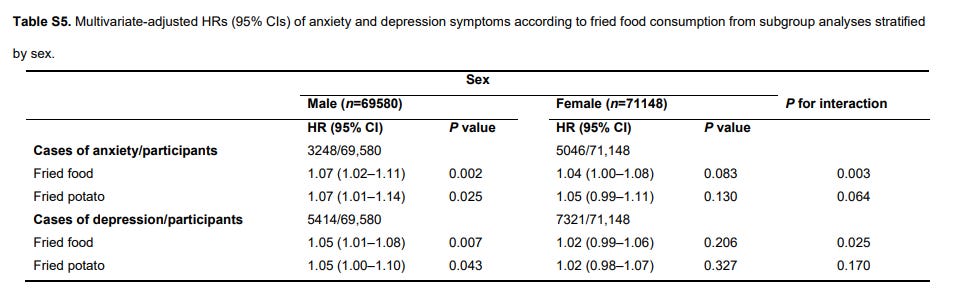

Let’s look at the study in PNAS itself. First, they state very obviously that there was an ASSOCIATION between French fry and other fried food consumption and anxiety or depression. They report it as a hazard ratio (HR), which means, they divide the occurrence in the ‘test’ group with the occurrence in the ‘control’ group. A HR of 1.0 means there is no difference.

So, in this figure, they’re claiming that there was a 12% higher risk of anxiety and a 7% higher risk of depression. First, that is not even what the data say! The highest hazard ration was 1.07, which is 7% increased risk (anxiety) and 1.05 for depression.

Next: this is ASSOCIATION. Not causation. We know that mental illness can alter dietary and food patterns; some individuals tend to eat more, some eat less. They insinuate that the mechanism here is due to acrylamide that is present in fried foods, but they use zebrafish as their model to make these claims. Not relevant to humans.

Other claims associated with consumption of the popular definition of UPF include:

Obesity and Weight Gain: Studies have found a correlation between UPFs consumption and increased risk of obesity. One controlled trial suggested that participants on a diet high in UPFs consumed more calories and gained more weight compared to those on a minimally processed diet, but this paper was actually criticized by several experts in the field, you can read those comments here. Ultimately, we know that if you’re consuming more calories than you expend, that can lead to weight gain. If those calories are from foods that have higher caloric/mass ratio, it can be easier to do that without realizing.

Cardiovascular Diseases: A cohort study in BMJ found that higher consumption of UPFs is associated with higher risks of cardiovascular diseases. Again, association, not causation, and the proposed relationship was increased intake of fats, salts, and sugars, none of which are unique to UPFs.

Type 2 Diabetes: Observational studies have shown an association between high consumption of UPFs and an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Type 2 diabetes is primarily a disease of metabolic dysfunction associated with obesity, so again, weight gain is not unique to consumption of UPF.

Cancer: Some observational studies suggest a link between UPFs and increased risks of certain types of cancer. However, these were not causal investigations and there are a variety of confounding variables, including overall diet and lifestyle habits and genetic predispositions.

Gut Health: Claims that UPFs can negatively impact gut microbiota are unsubstantiated. If you recall from our microbiome discussions, changes in microbiota cannot be used to make diagnostic inferences, as these are living organisms that are continually changes and responding to their environment, including the fuel they are provided.

There are other factors as well. Many studies that assess potential health impacts of ultra-processed and processed foods do not factor in how much of these foods are consumed. The amount of processed foods consumed as a proportion of one's diet is a gradient, and not all ultra-processed foods are low in nutrients.

It's important to note that while these studies show associations, they do not definitively prove causation. Factors such as lifestyle, overall dietary patterns, and genetics also play crucial roles in these health outcomes. Moreover, people who consume higher amounts of UPFs might also engage in other behaviors that contribute to poor health, such as lower physical activity levels.

Why can’t we all just eat less processed foods?

Fresher and less processed foods are typically more expensive and have a shorter shelf life than more processed foods, making it more difficult for those with fewer financial resources to spend on food.

Food deserts (areas where it is difficult to reach healthier food options) make it more difficult to access fresh and less processed foods.

On top of increased cost, the increased distance to get to these foods makes it even less feasible for lower-income people to obtain them.

Many processed foods are nutritious (e.g. frozen fruits) and often are more accessible options for people who lack access to fresh foods.

There is not a direct relationship between whether a food is processed and its nutritional content.

Not all processed foods are unhealthy. Even those that are less nutrient-dense are perfectly fine to consume in moderation. Ultra-processed foods that lack important nutrients such as fiber, protein, vitamins, and minerals should not be a major part of our diet, as we know those substances are beneficial for a variety of health outcomes. But we need to do away with this demonization of food simply for being food. Consuming ultra-processed foods in moderation is not going to be particularly impactful to your health. Remember: the dose makes the poison with everything, and that goes for foods as well.

If you have an overall health lifestyle, exercise regularly, eat an overall diverse diet, get your preventive screenings, stay up-to-date on vaccines, practice good hygiene, a “UPF” here or there (even one a day!) is not going to harm you.

You know what will cause harm? Excessive health anxiety and fear about foods that are perfectly safe.

Thanks for joining in the fight for science!

Thank you for supporting evidence-based science communication. With outbreaks of preventable diseases, refusal of evidence-based medical interventions, propagation of pseudoscience by prominent public “personalities”, it’s needed now more than ever.

Your local immunologist,

Andrea

This is very interesting.

Sorry in advance for all the asterisks, but there's no option for italics in this text box.

Having read Ultra Processed People, the evidence for the *associations* does seem compelling, but it seems the mainstream media is not able to pick up the nuance around this. I don't recall from the book if there was an emphasis around *association* rather than causation, so I may re-read looking for this specifically.

That said, one of the things I did take away from that book is the potential that the additional processing for taste and engineering to encourage consumption of certain foods seems to make them easier to eat in larger quantities than intended, thereby potentially making them more difficult to consume in moderation.

I have long shared the concern that these foods are often cheaper and easier to get and usually easier to prepare/eat, especially in food deserts and areas affected by poverty. It seems that more may need to be done to make fresher foods more accessible so that *everyone*, regardless of socioeconomic status, has the ability to *choose* how much they eat from every/any category of food. The food industry is significant, and the effect of lobbying is alarming. It would be nice to see the level of investment in ensuring corporate profits matched or exceeded by funding to make a greater variety of food available to everyone.

I'm interested to see how this particular concept evolves and how our understanding of diet and nutrition as they relate to long term health continues to grow.