The USA exists because of vaccines. Vaccinations: patriotic since 1776.

Happy Independence Day!

Today, July 4th, marks Independence Day here in the US: the day that commemorates the Declaration of Independence, ratified by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. This effectively established the United States of America.

The Declaration of Independence served as a legal severance to the subordination of England and the monarch, and as such, underpinned the Revolutionary War, which had been ongoing since April 1775 after the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

(Note: for any history enthusiasts who want to learn more about this period, check out 1776 by David McCullough and A People’s History of the American Revolution by Ray Raphael)

Anyway, as you celebrate today, a reminder:

Without vaccination, it is likely that the USA would have lost the war and we might not be a country today.

Smallpox was sweeping North America in the 1700s.

Smallpox, now eradicated from the planet (aside from stockpiles in very secure BSL-4 laboratory facilities) was a very serious and fatal disease. Caused by the Variola virus, smallpox could cause mortality rates up to 90% depending on the disease manifestation, with an average mortality rate of 30%.

Variola virus is incredibly environmentally stable: it can remain infectious in scabs and in clothing and bedding for up to a month. In the era of less than optimal hygiene, this meant that the virus was easily transmitted person to person, through clothing and contaminated objects, and even through contact with household items and surfaces.

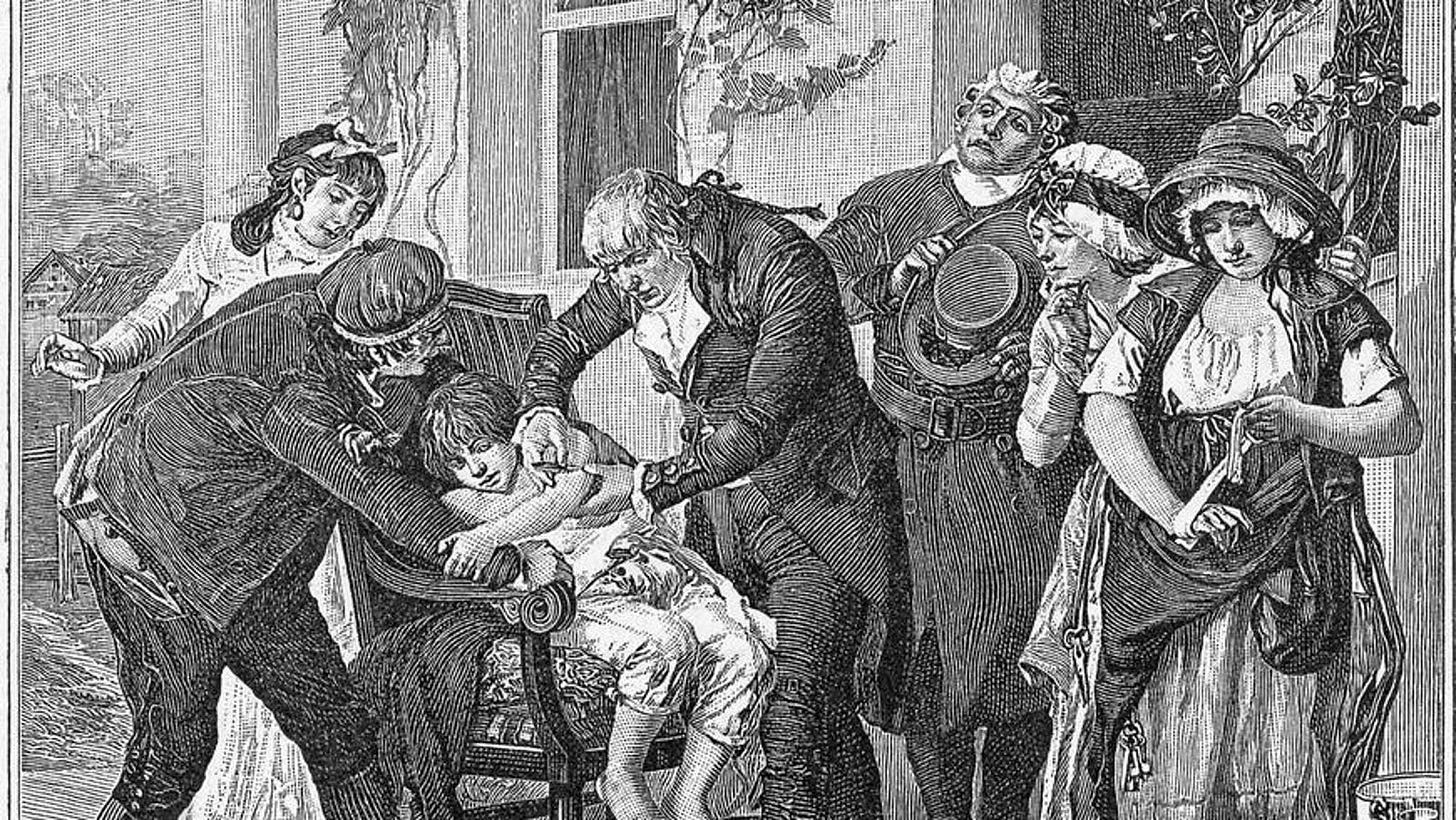

Variolation provided immunity to smallpox.

In the 1700s, the method of providing immunity to smallpox was through variolation, considered the first “vaccination”. This was performed by doing an intentional inoculation with the Variola virus. There were different methods, but the original method involved taking smallpox scabs - filled with virus - drying them over a fire, grinding them up, and blowing it up peoples’ noses. The process of variolation evolved over time. By the mid-1700s variolation methods also included introducing smallpox pustule material into a cut on the arm or using contaminated cloths as bandages.

Variolation had some issues. Remember: this was not a vaccines of today: this was intentional inoculation with a potentially fatal virus.

However, because it was performed under more controlled methods, and using certain criteria, variolation led to about 2-3% mortality compared to the 30% of smallpox. After successful variolation, the person was immune to smallpox.

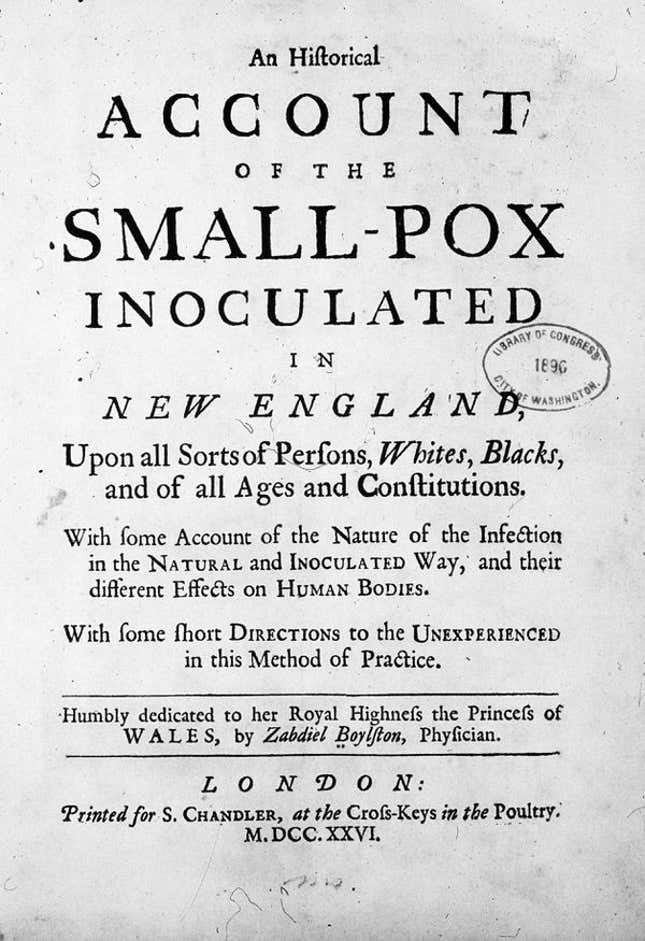

In 1721, a huge outbreak of smallpox in Boston caused 844 deaths. During the epidemic, physician Zabdiel Boylston, at Cotton Mather's urging, variolated 248 people, thereby introducing variolation to the Americas. Mather learned of this technique through an African man named Onesimus who was enslaved by Mather.

Onesimus had been variolated before being captured and taken to Massachusetts, and he described this procedure to Mather. Onesimus stated “whoever had the courage to use it was forever free of the fear of contagion”.

As I’m sure you can guess, there was quite a bit of anti-variolation sentiment for a variety of reasons. Racism was a common one: many of the colonists would not trust the words of an enslaved Black man, including Cotton Mather. It wasn’t until he verified that this practice was being implemented elsewhere that he trusted it.

Onesimus’ knowledge paid off: during that outbreak, only 6 people who died were variolated. In contrast, smallpox itself had a fatality rate of 14%.

Even Benjamin Franklin was opposed to variolation. But in 1736, he lost his 4 year old son to smallpox, and he lamented he didn’t variolate him.

“In 1736 I lost one of my sons, a fine boy of four years old, by the smallpox taken in the common way. I long regretted bitterly and still regret that I had not given it to him by inoculation. This I mention for the sake of the parents who omit that operation, on the supposition that they should never forgive themselves if a child died under it; my example showing that the regret may be the same either way, and that, therefore, the safer should be chosen.”

Afterward, Franklin became an advocate for variolation. However, because variolation still had risks associated with it and someone who had been recently variolated could infect others, there was ongoing hesitancy up through the Revolutionary War.

Smallpox was decimating the Continental Army.

Smallpox was severely impacting the population of North America, including the Continental Army. While many Americans did not have immunity from prior exposure, many of the British soldiers did, meaning the Continental Army was disproportionately impacted by the devastation of smallpox. At this point, variolation was still opposed by many, including George Washington, who was concerned the deliberate exposure of troops was too much of a risk.

Unfortunately, smallpox was a bigger risk. It is estimated that smallpox killed 10% of the army during the Siege of Boston in 1775.

It got worse.

During the Canadian Campaign led Benedict Arnold and Richard Montgomery to attempt to seize Quebec in 1775-1776, nearly half of the troops were infected with smallpox. The harsh winter conditions, poor nutrition, and exposure to virus led to rapid spread of disease through the camps. The death toll is estimated to be as high as 5,000, and smallpox is considered to be the primary contributor to the failed siege on Quebec.

Benedict Arnold forbade variolation to his troops, and in the early months of 1776, many who survived smallpox fled Quebec when their enlistments were up, further weakening the forces.

At this point, smallpox was causing more deaths than combat itself, and even among those who survived illness, they were often too weak to fight for quite some time. Even John Adams recalled to his wife that they were defeated by the British in Canada because of smallpox, not because of the British forces.

As a result, Washington made a decision:

The comparatively small risks of variolation were worth it as smallpox raged through the Continental Army.

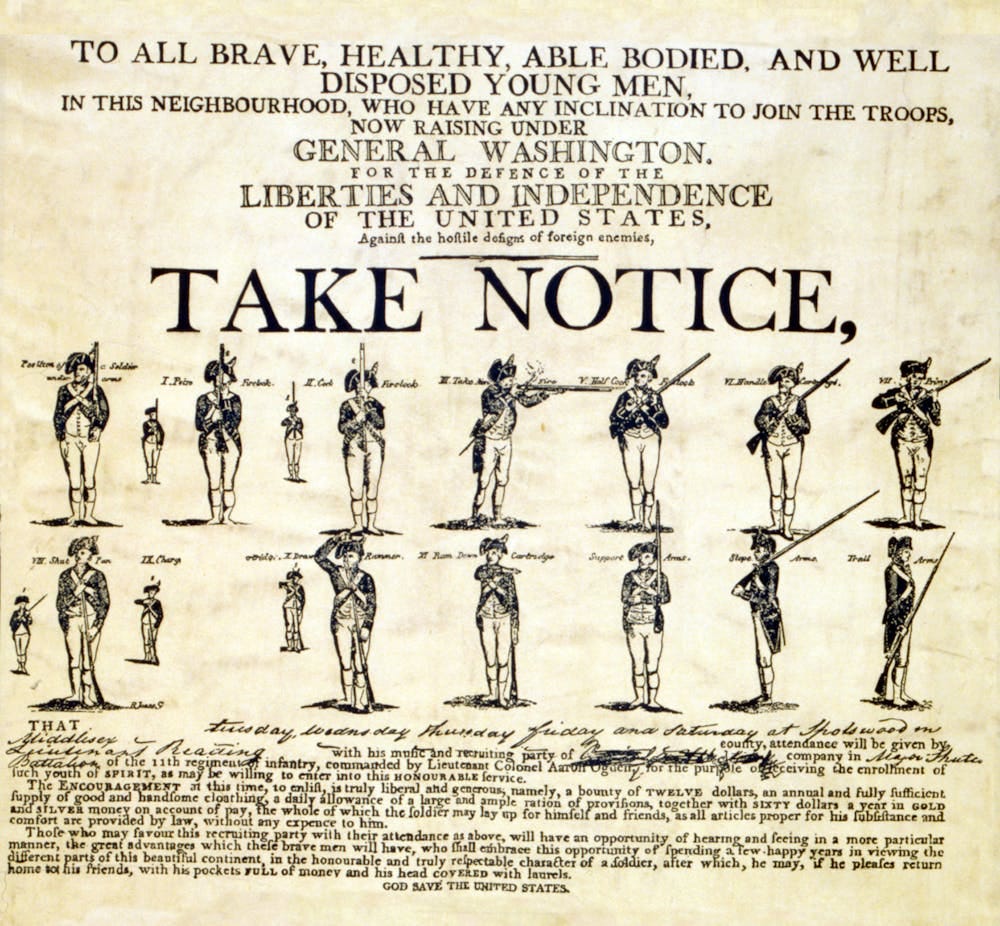

Public health literally started with the birth of the USA. Less than 6 months after the Declaration of Independence was ratified, in January 1777, George Washington mandated that all troops fighting for the Continental Army must be inoculated against smallpox.

He also instructed Dr. William Shippen Jr, Medical Director of the Continental Army, to variolate all new recruits coming through Philadelphia so they would not be at risk to the efforts or potentially infect others in the states.

Finding the smallpox to be spreading much and fearing that no precaution can prevent it from running thro’ the whole of our Army, I have determined that the Troops shall be inoculated. This Expedient may be attended with some inconveniences and some disadvantages, but yet I trust, in its consequences will have the most happy effects. Necessity not only authorizes but seems to require the measure, for should the disorder infect the Army, in the natural way, and rage with its usual Virulence, we should have more to dread from it, than from the sword of the enemy.

Washington’s smallpox immunization mandate was the first large-scale public health initiative in US History.

Washington understood the importance of troops to be ready for combat. He recognized that being healthy, able-bodied, and well disposed meant protected against serious and deadly diseases.

After his mandate, the health of the Continental Army improved dramatically. The inoculation campaign reduced the incidence of smallpox and contributed to the troops readiness and effectiveness as the Revolutionary War continued. Now that American troops were more protected than British troops, they were able to take strategic advantage.

Smallpox inoculations saved the Continental Army and helped the US win the Revolutionary War to gain independence from England.

Indeed, many historians attribute George Washington's smallpox inoculation mandate to the outcome of the war. Without the protection it conferred, it is entirely possible that the troops would have been too depleted and weakened during the following years and would have been overwhelmed by the British.

Vaccine Mandates since the birth of our country...literally

The impact of smallpox on the Continental Army during the first years of the war led to a dramatic shift in policy and outlook. This perspective held following the conclusion of the war and shaped future public health policies for US military and the country on the whole.

Beginning in 1796, soldiers received the smallpox vaccine, keeping troops safe from the disease from the War of 1812 through World War II.

Vaccines for influenza, tetanus, cholera, diphtheria, plague, and yellow fever were added to the list of mandatory vaccinations for military personnel following World Wars I and II.

Yes, today, the US Military implements vaccine mandates:

Every branch of our US military requires that soldiers be mission ready to protect us at all times. Mission ready includes training, fitness, and health. A healthy unit that is ready to deploy or aid at home is one of the cornerstones of our military. Making sure that our soldiers are vaccinated against diseases that can spread to entire units is vital to this readiness.

Currently, the Department of Defense administers 17 different vaccines to prevent diseases that may put troops at risk here and abroad. They also fund and research vaccines and treatments for illnesses such as malaria, tick-borne illnesses, and hepatitis E.

Aside from routine vaccines and boosters, service members may also be required to be vaccinated for: Anthrax, Botulism, Campylobacter, meningitis, rabies, and others depending on where they are stationed.

A cornerstone of our Democracy and being a patriotic American is public health, including vaccinations.

We are living in a time where rejection of science is used as a battle cry for many who self-describe as patriots.

However, on this year’s Fourth of July, let’s take a pause amidst the festivities, to remember that this country was founded on the principles of public health and collective measures to ensure the safety of our troops and our citizens.

Happy Independence Day.

Thanks for joining in the fight for science!

Thank you for supporting evidence-based science communication. With outbreaks of preventable diseases, refusal of evidence-based medical interventions, propagation of pseudoscience by prominent public “personalities”, it’s needed now more than ever.

Stay skeptical,

Andrea

“ImmunoLogic” is written by Dr. Andrea Love, PhD - immunologist and microbiologist. She works full-time in life sciences biotech and has had a lifelong passion for closing the science literacy gap and combating pseudoscience and health misinformation as far back as her childhood. This newsletter and her science communication on her social media pages are born from that passion. Feel free to follow on Instagram, Threads, Twitter, and Facebook, or support the newsletter by subscribing below:

Had not a single clue inoculation actually went that far back. So cool! Gross to think of snorting cooked scabs. 😆