The mpox outbreak in Africa is declared an international public health emergency

No, this is not the start of a pandemic. No, you don't need to panic. Here's what you should know.

Mpox has recently been declared a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). While headlines are rampant, let me assure you: this is not another COVID-19 pandemic.

A PHEIC is declared when the World Health Organization (WHO) deems it necessary to alert other global countries about a potential public health threat.

It serves to mobilize resources (often financial and healthcare) to respond to any public health issue that cannot be controlled by an affected country’s existing tools.

The reason this was done on August 14, 2024 in response to the mpox outbreak in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is similar to the response in 2022: cases are spreading beyond the region it is considered endemic, and international attention will enable a more coordinated and rapid response to control the outbreak. In 2022, this was initiated as a result of case reports in the UK, ultimately traced to an individual who contracted it in Nigeria. In this instance, the variant of the virus is a more transmissible and serious clade, increasing the public health concern.

Does this mean you as a person who does not live in sub-Saharan Africa in an area where there isn’t endemicity of mpox need to panic? No.

But let’s discuss some virology and immunology first, so you can understand why this outbreak is not going to be the next pandemic.

Mpox is caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV), also referred to as the mpox virus or Orthopoxvirus monkeypox.

It belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus, part of the Poxviridae family. This includes other viruses like variola virus (which causes smallpox), vaccinia virus (used in the smallpox vaccine), and cowpox virus.

MPXV was first identified in 1958 in laboratory monkeys. Formerly called monkeypox, it was renamed mpox in 2022 but the World Health Organization (WHO) for a few reasons. Scientifically, this was to eliminate confusion about the host range of the virus, because monkeys are not the primary host or reservoir for mpox. In actuality, non-human small mammals, especially rodents, are the natural reservoir for MPXV.

The first human case of mpox was reported in 1970 in DRC. Since then, mpox has been endemic in a number of countries in western and central sub-Saharan Africa, including:

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

Nigeria

Central African Republic

Cameroon

Republic of the Congo

Gabon

Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire)

Liberia

Sierra Leone

South Sudan

Since the 1970s, mpox has had patterns of pocket outbreaks in these countries and the case trends have shifted a bit. In the 1970s, cases were more commonly identified in younger children, whereas since 2010, cases are more commonly identified in young adults. However, until the early 2000s, case numbers were relatively low and restricted to these countries, but international travel and import and export of the virus has accelerated the spread (as it does with almost all infectious disease).

Mpox is related to the smallpox virus, which means it shares hallmarks of virology, pathology, and immunology

Mpox is closely related to smallpox. Before you panic, there are also some key differences, which makes the morbidity and mortality of mpox much lower than smallpox. But let’s take a walk through some virology and immunology.

Orthopoxviruses are transmitted by close and direct contact. Unlike viruses like influenza viruses and SARS-CoV-2 (and other coronaviruses), these are not spread by airborne transmission, but can be spread via close contact respiratory droplets.

While many of the cases in the US during the 2022 outbreak were linked to sexual activity, MPXV is NOT a sexually transmitted infection. Sexual activity is merely one route of person-to-person contact. MPXV spreads from any type of close contact:

Person-to-person physical contact (especially when lesions are present)

Direct contact with infected animals

Contact with contaminated objects

Symptoms of mpox progress over time with several key phases

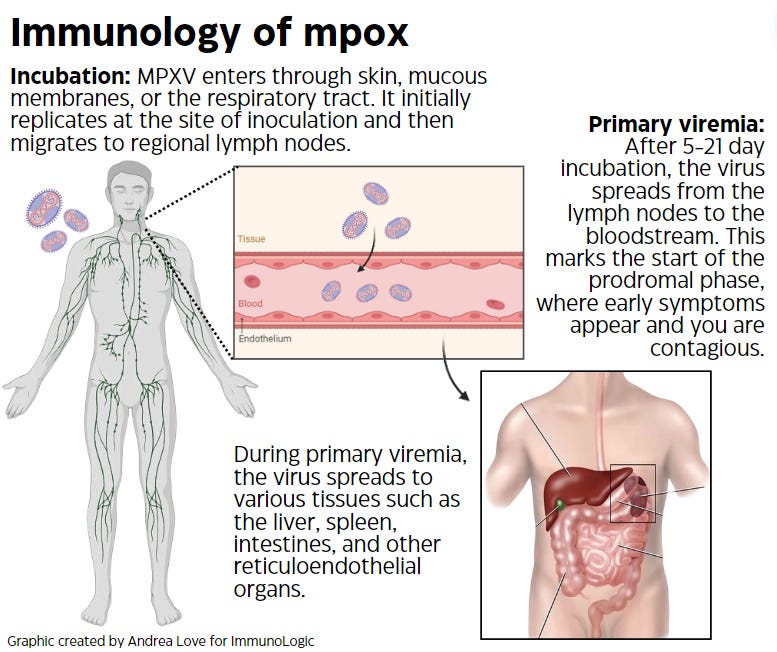

The incubation period of MPXV ranges from 5-21 days, with an average incubation period of 6-13 days. During this time, you are not contagious if you’ve been infected.

The incubation period is when the virus first enters your body and migrates to the regional lymph nodes to replicate. Once the virus replicates enough, it will leave the lymph notes to cause primary viremia: where the virus spreads in the bloodstream to other lymphoid organs. This is the start of the prodrome phase, which are the early symptoms that appear before the mpox rash.

The prodrome phase is marked by symptoms such as fever, headache, muscle aches, back pain, lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes), and fatigue. Lymphadenopathy is more common in mpox compared to smallpox and other poxviruses. The prodrome phase typically lasts 1-5 days before the characteristic rash appears.

Secondary viremia occurs when MPXV infects skin cells which leads to the characteristic rash associated with mpox. The rash typically begins on the face (sometimes inside the mouth) and then can spread to other parts of the body, most commonly the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.

Just like smallpox, mpox is characterized by skin lesions with 5 distinct phases during the secondary viremia phase:

Macules: Flat, red spots.

Papules: Raised bumps that develop from the macules.

Vesicles: Clear fluid-filled bumps that evolve from the papules.

Pustules: Vesicles fill with pus, becoming pustules, typically around 7-10 days after the rash appears. These pustules are round, firm, and deeply embedded in the skin.

Scabs: The pustules eventually form scabs. By the second week, most of the pustules have crusted over. The scabs then fall off, leaving pitted scars.

Mpox mortality is lower than smallpox.

Smallpox, now eradicated (thanks to vaccines) had an average mortality rate up to 30%. Because of the extent of the secondary viremia, the rapid spread led to severe progression of illness, systemic tissue damage, and organ failure. Mpox is not quite as virulent. Depending on the viral variant in question, mortality ranges from 1-10%, and disease pathology is less severe.

Mortality of mpox varies based on the clade of the virus

Clades refer to groups of related viral strains that share a common ancestor, as determined by genetic similarity. The more viruses evolve, the more potential clades may emerge, along with new strains (or variants) of a virus. In the case of MPXV, there are currently 2 major clades: I and II.

Clade I: Corresponds to the Central African (Congo Basin) clade. Clade I MPXV has a higher mortality rate, with an average case fatality rate (CFR) of 10.6%.

Clade II: Corresponds to the West African clade, and now is subdivided into clade IIa and IIb. Clade IIb was associated with the global outbreak seen in 2022. Clade II MPXV has a lower mortality rate, with an average CFR of 1-3.6%.

It’s important to note that mortality rates due to viruses like MPXV are dependent on the level of supportive care available. In developed nations, average CFR tend to be much lower than in developing and underserved nations for this reason.

The current outbreak is a concern because it is dominated by clade I MPXV, considered a high consequence infectious disease (HCID).

This outbreak spreading across African countries is of greater concern because the virus variants spreading are from Clade I, which can have a mortality rate nearly 10-times higher than clade II MPXV.

The current spread in western and central Africa is now extending to countries previously unaffected by mpox, including Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda. In addition, case rates are up by 160% compared to the same time last year, and deaths are up by 19%. To date, there have already been 517 deaths reported across African countries. This is likely an underestimation as a result of the reduced infectious disease surveillance resources in neglected countries compared to developed nations.

A day after the WHO issued the PHEIC, a case of mpox was reported in Sweden. Since then, the European CDC and the UK Health Security agencies have issued guidance for contact tracing, early detection, and monitoring of potential additional cases of mpox in European countries.

If you’re in the US, or any other countries where the outbreak is not ongoing, you do not need to panic, or rush out to get vaccinated.

Currently, any cases in the US of mpox are all clade II, a result of the diminishing spread of the 2022 outbreak. Cases of mpox in the US are low, with 1,657 cases reported in the US this year to date and 8 cases reported in the week ending August 10, 2024.

If you’re not planning to travel to any of the affected countries, you don’t need to track down a vaccine.

If you’re planning to travel to affected countries, but won’t be involved in medical response, you don’t need to track down a vaccine.

If you’re planning to travel to affected countries as a medical responder, you should get vaccinated.

If you’re planning to travel to affected countries, avoid things that are particularly high risk: interaction with wild animals, particularly rodents, close contact sexual activity with individuals where you don’t know their sexual history, and interacting with people with flu-like symptoms. That’s pretty much it. Because mpox lesions appear relatively quickly after the prodrome symptoms, there isn’t a significant window between generic symptoms of mpox (where it could be mistaken for something else) and the macule formation.

Why is Europe on alert, then?

European nations are much closer geographically to endemic countries in Africa. As a result, there is much more frequent travel between those countries. That, plus the already detected case in Sweden, means that those countries want to be armed in the event that spread continues. However, even within those countries, public health officials have stated that the overall risk is quite low.

Effective vaccines can prevent mpox, but we need to get those deployed to the countries that need them.

There are several vaccines currently available across the globe that prevent both smallpox and mpox, due to how closely related the viruses are. In the US, there are specific recommendations for those at highest risk, but for the most part, most individuals here have no need for mpox vaccination.

JYNNEOS® vaccine (also called MVA-BN®, Imvanex, and Imvamune) is approved by the US FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to prevent smallpox and mpox. It is the primary vaccine used for mpox since the outbreak in 2022, where many countries began stockpiling it.

Lc16m8 (LC16m8) is a similar technology to MVA-BN, but is currently only approved in Japan.

MVA-BN is an attenuated (weakened) vaccinia virus vaccine that cannot replicate in human cells, which increases the safety profile for individuals with compromised immune systems or other health conditions, who are at higher risk for severe illness due to mpox.

Other vaccines are also available, but many use live (non-attenuated) vaccinia virus and can be associated with increased reactogenicity compared to JYNNEOS. As such, there are generally reserved for specific emergent situations:

ACAM2000® vaccine is licensed to prevent smallpox and recommended by the ACIP for certain people at risk for exposure to orthopoxvirus infections.

Aventis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine (APSV) is also a live vaccine virus vaccine, but is currently in investigational use only. If an emergency situation presented itself, it could be authorized under EUA.

African countries need support from the rest of the world

Herein lies the crux of the motivation behind issuing the PHEIC.

Mpox is considered a neglected tropical disease, but with the outbreak in 2022 that led to over 100,000 cumulative cases, especially in the US, mpox has now gotten global attention.

Is the silver lining of that the potential for those in poorer and developing nations to be included in proactive measures to combat and control a disease that has impacted them for decades?

Our world is interconnected, whether people want to acknowledge it or not.

While currently, this outbreak of clade I mpox is majority restricted to African countries, that doesn’t mean it can’t change, exactly as it did in 2022. Humans don’t live in a bubble, and that is a commonality with communicable illnesses. With increased international travel, globalization, and other factors, it is imperative that the world take coordinated efforts to stop the spread of emerging infectious diseases.

To that end:

The US Agency for International Development (USAID) has provided $424 million in preparedness and response support to CDC Africa in recent months, to assist with both humanitarian and medical aid. The US has donated 50,000 doses of the Jynneos vaccine to the DRC, where 96% of the Clade I cases are currently being reported.

The European Commission’s Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority (HERA) and Bavarian Nordic have signed agreements with African CDC to provide over 215,000 doses of MVA-BN®, where equitable distribution across those countries with highest needs will be overseen by African CDC.

But those donations alone aren’t sufficient. It is estimated that over 3 million doses of vaccine in the DRC alone are required, and Africa CDC has stated they need at least 10 million doses.

Yesterday, (USAID) committed to donate another $35 million toward the efforts.

Japan has also offered to donate vaccine, but how many doses, we don’t yet know.

Gavi, the global vaccine alliance, has stated they have $500 million to spend for acquisition and allocation of vaccines.

The company that manufactures JYNNEOS, Bavarian Nordic, is readying their facilities to largescale manufacturing. They have stated they will be able to supply 2 million doses by the end of this year, and up to 10 million by the end of 2025.

Have some lessons been learned from the 2022 mpox outbreak and COVID-19? Possibly.

How the international response to this will play out, only time will tell. However, if you are not among the individuals at highest risk for mpox, you do not need to panic. All of us, as members of society, should understand that infectious diseases affect all of us, which is why anti-vaccine rhetoric, refusal to comply with mitigation measures, and limited resources can, and do, impact society.

Thank you for supporting evidence-based science communication. With outbreaks of preventable diseases, refusal of evidence-based medical interventions, propagation of pseudoscience by prominent public “personalities”, it’s needed now more than ever.

Stay skeptical,

Andrea

“ImmunoLogic” is written by Dr. Andrea Love, PhD - immunologist and microbiologist. She works full-time in life sciences biotech and has had a lifelong passion for closing the science literacy gap and combating pseudoscience and health misinformation as far back as her childhood. This newsletter and her science communication on her social media pages are born from that passion. Follow on Instagram, Threads, Twitter, and Facebook, or support the newsletter by subscribing below:

"Our world is interconnected, whether people want to acknowledge it or not."

Sadly, as someone looking in from outside the USA, political polarization within the USA driven by DJT reinforces the misconception our world is not interconnected...as seen through my lens.

Blow-hearts & their megaphone can be quieted by the much larger populist(s) which speaks truth to truth, not unlike Dr. Andrea's (voice) & many others who contribute to the various Substack postings.

I'm at risk of making a "political statement" (I cannot vote in the USA) and not my intent... we are one world more interconnected with each technical advance (every plane ride). The challenges presented with current mpox epidemic is underscored by the concept of One Health.

Dr. Andrea your explanation presented is very informative and added to my understanding of what I have been following, thank you.