Measles: Is it Immune or Human Amnesia?

People have really forgotten the impact of preventable illness

It is fitting that the first official piece here is about measles: a vaccine-preventable infectious disease. At this very moment in January 2024, SIXTY ONE years after the first measles vaccine was approved, we are still dealing with entirely avoidable outbreaks of this communicable illness.

Currently: there is an outbreak in the Philadelphia metro area (where I live), one in the DC metro area, and another in Washington state. There is a sustained outbreak in the Birmingham area of U.K. where 216 confirmed and 103 probable cases have been reported, and at least 50 children have been hospitalized since October 2023.

The common thread? Low vaccination rates and import of the disease by unvaccinated travelers.

Last year, there were 1,603 reported measles cases in the U.K., more than double those reported in 2022 (735), which was more than double those reported in 2021 (360).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has raised alarm about the dramatic increase in measles morbidity and mortality. There were substantial outbreaks in 37 countries in 2022 (compared to 22 in 2021), and cases increased by 18%. There was a 43% increase in deaths due to measles compared to 2021, with the majority of them among children. This does not have to be our reality.

The Pan American Health Organization alerted alliance countries to update plans to prevent the re-establishment of endemic measles. While the United States was declared free of endemic measles in 2000, increased anti-vaccine sentiment and dropping vaccine rates jeopardizes that status.

It is heartbreaking that this is the state of affairs with a widely available vaccine with 97-99% effectiveness. Today, it takes conscious effort to avoid measles vaccination and this rejection is eroding our collective health and well-being.

Last year, the CDC reported the highest level of vaccine exemptions for kindergarteners ever recorded; nearly all were listed as ‘non-medical’. On top of that, there are people like the midwife on Long Island who administered fake ‘vaccines’ to thousands of children so parents could falsify school vaccine records. Is it really any wonder that we are seeing spread of this disease we thought we had under control?

Measles is a very contagious respiratory viral infection

Measles (Rubeola) is a highly contagious disease caused by infection with the measles morbillivirus (MeV). It is one of the most contagious viral illnesses in humans. In a non-immune population, someone infected with MeV will infect, on average, 12 to 18 people. Put another way: someone with measles can infect up to 90% of susceptible individuals they come in contact with.

MeV first infects immune cells (alveolar macrophages and dendritic cells) in the upper respiratory tract and spreads systemically by hitching a ride to lymphoid organs like the spleen, lymph nodes, adenoids, and tonsils. While in those tissues, the virus spreads to lymphocytes, the B and T cells of our adaptive immune system. The infected immune cells transport virus back to epithelial cells in the respiratory tract, where the virus exits the body to infect others.

MeV is transmitted primarily through airborne routes: the virus is released into respiratory droplets when someone sneezes, coughs, or breathes. The smaller droplets can remain suspended and travel in the air and for several hours, which contributes to the high transmissibility of MeV.

After exposure, MeV has a average incubation period of 12 days (range 7-14 days). Initial symptoms are fever (which can be as high as 105F), cough, runny nose, and conjunctivitis. Koplik spots (whitish-blue spots inside the lips and cheeks) also appear. The measles rash appears 2-4 days after: a flat red rash that starts at the hairline, spreads down the face, neck, torso, and extremities. People who are infected with MeV are contagious starting about 4 days before the rash appears (often when only early symptoms present). This means people may expose others before they know they have measles, further contributing to viral spread.

Measles vaccines save MILLIONS of lives every year

Prior to 1963, measles led to serious epidemics every couple of years and caused on average 2.6 million deaths annually (when the global population was much lower; for context, it was 3 billion in 1960, compared to 8.1 billion today).

Mortality rates vary based on access to supportive care, but range from 0.1% to up to 10% in areas with lower access to care. 30% of measles cases lead to serious and potentially permanent complications, including pneumonia, blindness, hearing loss and deafness, severe diarrhea and dehydration, and encephalitis (brain infection and swelling).

Encephalitis occurs in about 0.3% of measles cases, and can potentially fatal as is. But another complication of measles is Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis (SSPE), a progressive, disabling, and deadly brain disorder that occurs following primary measles. It occurs in up to 18 of every 100,000 measles cases, with the highest risk among children under 5. There is no cure or treatment for SSPE, and it is fatal within 1-3 years of diagnosis. SSPE, along with measles itself and other associated complications, is entirely preventable now.

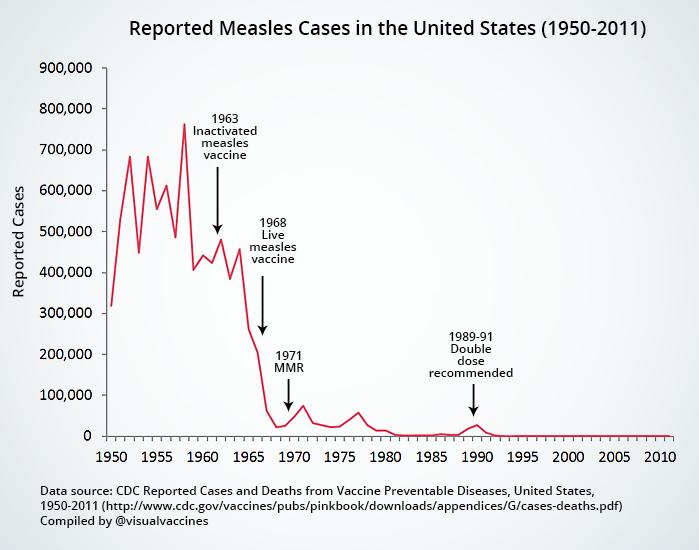

It is preventable because we have very safe and effective vaccines for measles. The first measles vaccine was approved for use in the United States in 1963. After the introduction of the measles vaccine, measles cases plummeted in the US and globally.

In the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, pockets of measles outbreaks occurred. These were primarily due to to low vaccination rates in certain areas or populations. During a surge in the late 80s, the 2-dose regimen of MMR was adopted. But this chart paints a clear picture: measles vaccination wiped out measles. (We will save the story of Andrew Wakefield, his falsified data, and dangerous lies for another time)

Globally, measles vaccines are estimated to have prevented 56 MILLION deaths between 2000 and 2021. Alongside that, measles was declared eliminated in the U.S. in 2000.

This doesn’t mean there aren’t measles cases in the US; it means there is no longer endemic measles (that exists within the country). Measles outbreaks that occur are initiated by international import by an unvaccinated (or non-immune) person, and are spread when they encounter other unvaccinated individuals. Declining vaccine rates as a result of anti-science disinformation, complacency, and people forgetting the importance of vaccines have increased the frequency and range of these episodic outbreaks.

The vaccine is phenomenally effective but we need almost the entire population to be vaccinated to prevent outbreaks because of how contagious MeV is. The more contagious a pathogen is, the higher the herd immunity threshold is in order to keep the spread in check. In the case of measles we need 95% of our population to have immunity to MeV to prevent outbreaks and spread of illness.

If the vaccine is so effective and I’m vaccinated, then why should I care if measles is spreading?

Aside from the fact that is a wholly selfish attitude toward something that impacts collective society (see, I told you there would be some snark), there are people who don’t have immunity that we ALSO care about protecting. First: kids are not protected, and they are at the greatest risk for severe outcomes. The current vaccine for measles is either the combination MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) or MMRV (measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella). It is a 2-dose regimen, with dose 1 administered at 1 year old, and the second dose between 4-6 years old. As such, kids aren’t fully protected until that age. There is also a small proportion of people who, even after vaccination, do not develop robust immunity. There are also people who are immunocompromised, older adults, and those with underlying medical issues who may be at high risk for severe outcomes.

Immune amnesia: measles damages immune memory

Remember above where I mentioned that MeV likes to infect immune cells? Well, after they hitch a ride in the innate immune cells to those lymphoid organs, MeV then infects adaptive immune cells: the B cells and T cells (lymphocytes). These are the cells that establish memory immunity, and not just memory immunity to measles, but to any previous infections and vaccinations. When MeV infects these B and T cells and replicates within them, the virus ultimately damages and destroys the cells themselves plus the ability of the B cells to produce protective antibodies. This leads to immune amnesia: broad impairment to memory immunity as a result of the damage MeV infection causes.

When MeV eliminates these memory immune cells, this weakens your defense against previously encountered pathogens or pathogens you’ve been vaccinated again, rendering you susceptible to other infections and illness, and this can persist for years after measles.

Getting measles can effectively erase the immune memory that someone has developed against other pathogens.

Let’s use a scenario to illustrate this.

Hypothetically, say a child gets measles from an unvaccinated person when they are 3 years old. They are too young to have completed their measles vaccine regimen, but have been vaccinated for Hepatitis B, DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis), Rotavirus, Poliovirus, Influenza, COVID-19, Hepatitis A, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), Pneumococcal bacteria, Varicella (1 dose at least), and maybe RSV.

So this child has measles and hopefully will recover from that without long-term complications, and is now ALSO at risk of losing protection for all of these other illnesses, many which can be very serious at their age.

Let’s be clear: measles is much more than just a transient infection: its capacity to increase susceptibility to other infections due to immune system damage is a long-term risk to individuals and public health, underscoring the importance of vaccination even more.

Anti-vaccine disinformation is a top 10 global health threat.

If health agencies around the world don’t rapidly implement coordinated global efforts to increase vaccine rates, we may soon be in a position, once again, where measles outbreaks are the norm, not the rarity.

If you know someone who is hesitant or resistant to the MMR vaccine, please send them my way; I’d be happy to address legitimate concerns.

As always, thanks for joining in the fight for science!

Thank you for supporting evidence-based science communication. With outbreaks of preventable diseases, refusal of evidence-based medical interventions, roadblocks to scientific progress that improve food and crop sustainability, it’s needed now more than ever.

Yours in science,

Andrea