It’s the Most Violently Ill Time of the Year

Norovirus is back, it's brutal, and it doesn't care about your hand sanitizer.

RFK Jr., Marty Makary, and their anti-science allies continue to cause irreparable damage to our science institutions and public health systems. While there is much more to discuss on that, it’s worth remembering that even as they dismantle decades of scientific progress, the health foes we face still exist. And given that our health agencies have been co-opted by propaganda, it’s more important than ever that all of us have access to reliable and factual information about health issues that impact everyone.

As our institutions are being weakened by political theater and conspiracy-driven interference, microbes aren’t taking a gap year. They are very much still out there doing what microbes do best: exploiting human vulnerability to survive. Which brings us to a timely—and very real—threat making the rounds right now: norovirus.

Norovirus is once again sweeping the country—and, unsurprisingly, cruise ships.

So far this year, there have been 16 norovirus outbreaks on CDC-regulated cruise ships (plus 5 other GI outbreaks of unknown or alternative origin). And yesterday, yet another cruise ship reported an outbreak.

About 5% of on board passengers have become ill. That may not sounds great, but given how contagious norovirus is and how ideal a breeding ground a cruise ship is…things could be far worse.

But with the holidays approaching and cases rising sharply across the country, we should all understand how to protect ourselves from a violent, wildly unpleasant, and potentially dangerous pathogen (one we still don’t have a vaccine for).

Noroviruses are the leading cause of acute gastroenteritis in adults.

Acute gastroenteritis simply means inflammation of the stomach and intestines, most commonly caused by viral infections—primarily norovirus and rotavirus. In children, rotavirus beats norovirus as the most common cause, but we do have a very effective vaccine for rotavirus which has dramatically reduced hospitalizations and deaths.

Bacterial infections (usually toxins produced by bacteria) come in behind viral infections. Other pathogens, such as parasites like Giardia lamblia and Cryptosporidium spp. are less frequent causes.

Symptoms of gastroenteritis include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain. Other symptoms like fever, lethargy, dehydration, and complications associated with those can occur.

Illness caused by norovirus is fast and furious

In the case of norovirus, if you get infected, you’re going to know it—and quickly.

Symptoms from norovirus develop between 12 and 48 hours after exposure and are typically violent in onset and nature (yes, I am speaking from both personal and professional experience).

These include:

Nausea

Acute-onset vomiting

Watery, non-bloody diarrhea

Abdominal cramps

Fatigue, muscle aches, headache, and fever can also be present.

If you’ve been there, you know what I’m talking about. Now, there is some good news.

For most people, illness is “mild” in the medical sense—meaning symptoms resolve quickly (within 1–3 days) and without major medical intervention, not that it feels remotely mild while it’s happening. However, norovirus can be particularly serious for young children and older adults. Children under 5 years old and adults aged 85 years and older are more likely to have an outpatient or emergency department visit than people of other ages.

Norovirus is the number one cause of foodborne illness, the fourth leading cause of foodborne illness-related death, and is responsible for 58% of foodborne illness. Norovirus causes nearly 1 million pediatric medical visits every year in the US, and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality.

By 5 years of age in the US:

1 in 110,000 will die from norovirus

1 in 160 will be hospitalized

1 in 40 will go to the emergency department

1 in 7 will go to an outpatient clinic

These aren’t stats from an outlier season—this is what we see year over year. Norovirus is one of the most burdensome and costly GI pathogens we face. Globally, norovirus causes around 685 million cases of illness every year. In the US, it is estimated to cause up to 21 million cases of gastroenteritis annually. And unfortunately, we don’t yet have a vaccine for norovirus, in part because there are over 40 different strains of the virus.

Norovirus outbreaks are most common during winter: which means, right now.

Across the US, norovirus test positivity rates are around 14%, which is double the test positivity seen just a few months prior. Last year’s season was particularly bad, with test positivity rates of 25%. Wastewaster tracking, which monitors for presence of viral genetic material in sewage, indicates a similar upward trend of norovirus.

While people often call norovirus the “stomach flu,” it has nothing to do with influenza. Noroviruses belong to the calicivirus family and are non-enveloped viruses—a classification that explains much of their sturdiness.

Viruses are classified according to their structure and composition, which include their viral genome and the protein capsid. Viruses that only contain those pieces are considered non-enveloped, whereas viruses that have a lipid membrane that surround that protein capsid are enveloped (the lipid layer is the envelope).

Read more virology basics in the below:

Non-enveloped, or naked viruses like noroviruses tend to be more virulent than enveloped viruses. This is because that lipid membrane in enveloped viruses is critical to their function, but it is more fragile than a standalone protein capsid. As a result, non-enveloped viruses are more resistant to the elements and can withstand heat, humidity changes, and many disinfectants. Beyond noroviruses, other non-enveloped human viral pathogens include the enteroviruses, adenoviruses, and rhinoviruses.

Note: this newsletter is free, but it’s able to sustain itself from support I receive from a small percentage of regular readers. If you value science-based information, consider upgrading to a paid subscription:

Norovirus is extremely contagious.

Norovirus is pretty fascinating, from a microbiology and immunology perspective. Norovirus has the lowest minimum infectious dose of any known human pathogen. Fewer than 18 viral particles can infect you. That’s why norovirus spreads so efficiently. Norovirus is transmitted through multiple routes, both because of how contagious and sturdy it is. No big deal or anything, but norovirus can remain intact and infectious on surfaces for up to 4 weeks.

Norovirus spreads through:

Person-to-person contact

Fecal-oral routes (norovirus is shed in the stool)

Contaminated surfaces and objects

Food- and water-borne routes

And because so few particles are needed, even microscopic aerosolized droplets from vomiting can infect someone nearby. This is why outbreaks explode in enclosed environments. This also means if someone has norovirus and has diarrhea and they don’t thoroughly clean themselves, their hands, surfaces they touch…well, you get the idea.

As you can guess, outbreaks are most common in high-density areas where people are in close quarters. Enter cruise ships. And daycares. And retirement communities or skilled nursing facilities.

Foodborne norovirus is transmitted a few different ways: through shellfish or seafood harvested from waters that are contaminated with human waste, or through poor personal and food hygiene practices, where an individual directly contaminates food. For example, an outbreak last December was traced to a sushi restaurant in North Carolina, where over 240 people reported falling ill after dining there.

Another fun fact: even after you no longer have symptoms, you can shed infectious virus in your stool for several weeks. That means if proper hygiene measures aren’t continued after you are feeling better, infections can continue to spread within your household and communities.

Hand sanitizers do NOT work against norovirus.

This is true not just for the noroviruses, but for all non-enveloped viruses. The mechanism that alcohol-based hand sanitizers work does nothing for these pathogens.

Alcohols disrupt and dissolve lipid membranes. Ethanol (60-95%) and isopropanol, the alcohols found in hand sanitizers, disrupt lipid (fat) membranes of enveloped viruses. The alcohol molecules intercalate (insert in between) within the lipid membrane, which causes it to break apart. This envelope is required for these viruses to attach to and infect host cells: without it, they are non-infectious. Norovirus has no lipid envelope. There is nothing for alcohol to dissolve.

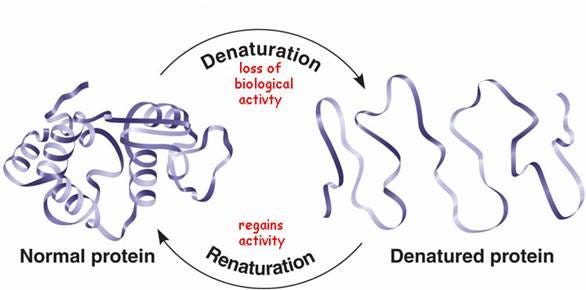

Alcohols also denature proteins. Denaturation is the process of unfolding a protein (called the tertiary structure). Viral proteins, including those required for attachment and entry into host cells are susceptible to denaturation. When these proteins lose their three-dimensional structure, they lose their function, effectively neutralizing the virus. Unfortunately, for many viruses, like noroviruses, the unfolding step isn’t enough to inactivate it.

You might be thinking, that viral capsid is made of protein, right? Why doesn’t sanitizer work on norovirus then?

Well, evolution equipped noroviruses to tolerate harsh environments far more extreme than your Purell bottle. Non-enveloped viruses like norovirus, adenovirus, rhinovirus, poliovirus, and HPV have really sturdy protein capsids, because that is the outermost structure of the virus. These proteins are incredibly resistant to things that would normally interfere with protein function, like stomach acid, ultraviolent radiation, desiccation (drying out), and yes, disinfectants.

Commercial hand sanitizers contain 60–80% alcohol. Norovirus requires at least 95% ethanol for meaningful inactivation.

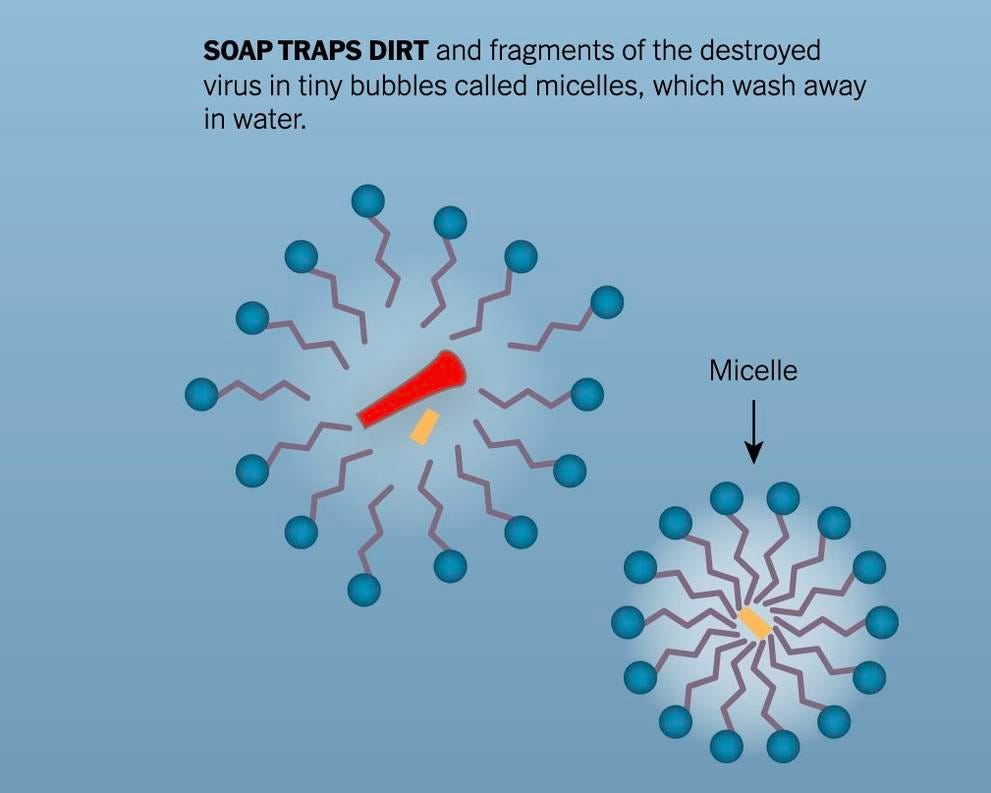

The solution? Wash your hands with soap and water.

Soap and water is the effective and preferred method for proper hygiene among the general public, especially if you’ve been in contact with fecal matter.

Detergents found in soaps form micelles (think of these like little fat cages) around pathogens which help remove them from your skin, trap them, and allow them to be washed away when rinsing with water.

What about cleaning surfaces?

There are many effective disinfectants for cleaning potentially contaminated surfaces. But that means you need to not listen to wellness influencers who tell you to use vinegar or other “homemade products” to clean your counters.

Spoiler: vinegar ain’t doing a damn thing to norovirus.

There’s a reason chemists and toxicologist and microbiologists are legitimate experts in these fields—they develop tools that improve hygiene and sanitation and protect our health. So let’s not fall prey to the appeal to nature fallacy, or rhetoric coming from the Washington Post about how you need to avoid “harsh chemicals” — I guarantee they don’t have a clue what they’re talking about.

To actually disinfect surfaces, you can use:

Bleach (Sodium Hypochlorite) is the most effective disinfectant against norovirus. Sodium hypochlorite works by denaturing proteins and disrupting viral RNA, much more effectively than alcohol. A solution containing 5-25 tablespoons of household bleach per gallon of water is recommended. The exact concentration may vary based on the surface and situation.

While sodium hypochlorite bleach is the number one choice, you can also use:

Hydrogen Peroxide at a concentration of at least 3% can be effective against norovirus. It acts as an oxidizing agent, damaging essential components of the virus.

Quaternary Ammonium Compounds, also known as “quats,” these compounds can be found in household cleaning products and some types of disinfectant wipes. They can be effective against norovirus but often need to be used at higher concentrations. (Note: this includes benzalkonium chloride, which is not as effective as bleach and requires longer contact time and higher concentration).

Accelerated Hydrogen Peroxide (AHP), a more potent form of hydrogen peroxide which is effective against a broad range of pathogens, including norovirus.

Certain Phenolic Disinfectants which are made of phenols, a unique class of alcohols. These are typically used in healthcare settings.

Alcohols above 95% concentration. While commercial alcohol-based hand sanitizers are not effective against norovirus, higher concentrations of alcohol in certain disinfectants (95%) can have some efficacy. However, their use is limited compared to other options like bleach.

Ultraviolet light, particularly UV-C, can be effective for surface disinfection against norovirus, although it’s more commonly used in healthcare settings than in households.

If you aren’t sure if what you have available is effective against norovirus, check the EPA list of antimicrobials for norovirus (this is the archived version pre-Trump administration). Whatever disinfectant you choose, surface must remain wet for the full recommended contact time. Simply spraying and wiping isn’t cutting it when it comes to noro.

So…what happens if someone at home has norovirus?

First, don’t panic. Second, you are going to have to be vigilant. Unfortunately, there is no vaccine for norovirus and treatment involves supportive care. But if someone at home has norovirus, it doesn’t guarantee everyone will get it, if you take steps to reduce the risk.

Hand hygiene, especially in any common areas and particularly in the bathroom and kitchen spaces. Soap and water is king here. This is especially important after using the toilet, after changing diapers (if applicable), and before eating, preparing, or handling food. If you think you’re washing too frequently, you’re probably washing the right amount.

Food hygiene is essential. It goes without saying the sick individual should not be touching common food or prepping food for others in the house, and, if possible, should not be in the vicinity when food is being prepared. You should also not prepare foods for up to 3 days after your symptoms subside. However, additional measures can also be taken. Thoroughly wash fruits and vegetables before preparing and eating them, especially if eaten raw. Ensure seafood is washed and cooked thoroughly: norovirus can survive “searing” and quick “steaming” and temperatures up to 140F. Any foods that are potentially contaminated from the sick individual should be discarded. You can also consider wearing clean gloves while handling food or interacting with a sick individual.

Disinfect surfaces immediately. Any surfaces which have been in contact with vomit or fecal matter should be disinfected as soon as possible. Use a chlorine bleach solution with a concentration of 1000–5000 ppm (5–25 tablespoons of household bleach [5.25%] per gallon of water).

Thorough and prompt laundry. Anything: clothing, linens, etc., that may be contaminated should be washed. Minimize disturbance of potentially contaminated fabrics (remember: 20 viral particles can infect someone), wear gloves while handling and wash hands thoroughly after touching. Wash items in the washing machine with the highest cycle length and machine dry (for additional heat sterilization) afterward.

Caring for the sick individual. If the individual is actively vomiting, having diarrhea, and may not have the best hygiene for whatever reason, consider wearing a high quality mask whenever you are in contact with them. This will reduce the likelihood of particles floating around that may contain virus. You can consider wearing gloves if providing care for them, and always make sure to wash your hands extra thoroughly after interacting with them. You might also change your clothes before and after being in contact with them, so you’re not tracking viral particles elsewhere (Note: these measures are what I employed when Bill was in the nursing home earlier this year when he got norovirus during an outbreak there).

If you do inevitably get sick, I wish you all the best, truly. Even if you’re otherwise healthy and not at high risk for serious illness and complications, it can be one of the most unpleasant illnesses you might experience. Just remember: while you are balled up in pain, cursing whoever infected you, know that the chaos will be over with in a couple of days.

And remember: viruses don’t care about conspiracies, politics, or wellness pseudoscience.

They care about biology. When public health is undermined, microbes fill the void. And they won’t wait for us to remember that science is what keeps them at bay.

We all must join in the fight for science.

Thank you for supporting evidence-based science communication. With outbreaks of preventable diseases, refusal of evidence-based medical interventions, propagation of pseudoscience by prominent public “personalities”, it’s needed now more than ever.

Stay skeptical,

Andrea

“ImmunoLogic” is written by Dr. Andrea Love, PhD - immunologist and microbiologist. She works full-time in life sciences biotech and has had a lifelong passion for closing the science literacy gap and combating pseudoscience and health misinformation as far back as her childhood. This newsletter and her science communication on her social media pages are born from that passion. Follow on Instagram, Threads, Twitter, and Facebook, or support the newsletter by subscribing below:

This is so helpful! Thank You!!

I’m curious what is known about the immune response to norovirus, and is there an effort toward vaccine development.