Chemophobia - the fear of chemicals - is a public health crisis

Low science literacy and lack of biology, chemistry, and toxicology knowledge exacerbates this global health threat.

When I think about science and health disinformation, there are obvious trends. Of course, they exploit health anxiety, which causes people to react illogically and emotionally, and throw critical thinking out the window.

But they all exploit something even more universal:

Nearly all science and health misinformation capitalizes on chemophobia.

Whether it is the recent “heavy metals in tampons” headlines, discussed here

Myths about vaccines containing mercury, discussed here

Claims that your Cheerios are contaminated with toxic pesticides, discussed here

The Dirty Dozen list and the purported harms of “synthetic pesticides”, here and here

Or fluoridated dental products being “toxic,” discussed here

Fallacies that aluminum salt-containing antiperspirants cause breast cancer and Alzheimer’s discussed here

Non-nutritive sweeteners like aspartame being harmful, here

The decades-old myth that the herbicide glyphosate causes cancer, here

In fact, I have a section of my newsletter tagged as chemophobia, so head here to see all the topics I’ve written about.

While the World Health Organization states that vaccine hesitancy is a top ten global health threat, I would say chemophobia is an even greater threat. Because chemophobia underlies vaccine hesitancy but also many other issues that impact global health.

Chemophobia is the irrational fear or aversion of chemicals.

Chemophobia leads people to believe that chemicals are harmful at any level.

Chemophobia gained traction back in the 1950s and 1960s, when pesticide use started to become publicly controversial.

Common statements stereotypical of chemophobia include things like:

I only want natural ingredients

Vaccines have too many chemicals

I can't pronounce those ingredient names

These messages become prevalent when circulated by media outlets, online influencers, and more. They evoke strong emotional reactions, which make people more likely to share false claims and less likely to fact check.

Multiple factors in our current digital era exacerbate chemophobia.

Clickbait media articles that fail to accurately present science or lack context of a risk. (Hello, tampon stories, anyone?)

The majority of the general public does NOT fact-check after reading articles like this.

Many of those who reshare those clickbait headlines are unqualified to assess the truthfulness, and often have millions of followers, accelerating the spread of chemophobia.

People tend to be more fearful of human-made risks than natural threats, so if you can demonize a manufactured substance (a tampon, a vaccine, a food product), you can gain traction by spreading scary-sounding claims.

But, this all shares a foundation:

Chemophobia starts with low science literacy.

Unfortunately, low science literacy, which includes basic understanding of chemistry, biology, and toxicology are the bedrock for the success of chemophobic tactics.

Here are some stats that might be shocking:

Only 28% of Americans are considered to have civic science literacy.

Civic scientific literacy (CSL) is the ability of a citizen to find, make sense of, and use information about science or technology to engage in a public discussion of policy choices involving science or technology.

What does that mean? That you can not only read or listen to information, but understand what you’re consuming, or use critical thinking skills to determine why these claims might be suspect.

Only 22% of high school graduates are considered scientifically literate, and only 17% of adults with only a high school diploma qualify as civically scientifically literate.

This isn’t unique to the USA, either. A 2019 survey-based study demonstrated that:

40% of Europeans would want to "live in a world where chemical substances don't exist"

30% report being scared of chemicals, and nearly all demonstrated a lack of basic scientific understanding.

82% did not know that table salt always has the formula sodium chloride, and the source of it, whether from nature or synthesized in a laboratory, is exactly the same.

91% did not realize that the concept of “toxicity” means the dose makes the poison for everything, regardless of the source and identity of a chemical.

This isn’t an isolated incident, either. A Royal Society of Chemistry report details:

58% of women and 45% of men don't feel confident enough to talk about chemistry

43% of people are not at all engaged or interested in chemistry

What’s more? Most people couldn’t recall thinking of chemistry beyond school memories. The majority of people have low awareness of how chemistry is relevant to them. 45% of individuals either disagree or are apathetic to whether knowing about chemistry is important to daily life, which is concerning since chemistry impacts you every single day.

The problem? Everything is chemicals, even you.

Chemistry is how EVERYTHING exists and functions. Without chemistry, there would be no biology. There would be no life. There would be no organisms.

Chemical does not mean "synthetic" or "toxic." All matter is made of chemicals - our bodies, the air, and everything else. There's no such thing as "chemical-free."

Chemophobia is coupled with other themes and logical fallacies.

For example, if you confront someone about the fact that everything is chemicals, they might reply with “well, I mean synthetic chemicals,” which is the appeal to nature fallacy (discussed here).

The appeal to nature fallacy is the false belief that natural chemicals are inherently better or safer.

But the source of a chemical, whether naturally-derived or entirely synthesized in a laboratory, has no bearing on its safety. Synthetic substances are chemically the same as their "natural" counterparts.

Vitamin C made in a lab is chemically the same as vitamin C isolated from fruit. And in case you’re curious, the official name for vitamin C is (5R)-5-[(1S)-1,2-dihydroxyethyl]-3,4-dihydroxy-2,5-dihydrofuran-2-one.

Lots of natural substances can be quite harmful at low doses. For example, Botulinum toxin, naturally produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, can be fatal if ingested at a dose as low as 0.0000000004 grams per kilogram.

Sarin, a nerve agent synthetically created in 1938, would be the closest in toxicity, and it’s lethal dose is 0.00055 grams per kilogram. Botulinum toxin is over 1 million times more toxic than any manmade chemical.

People even apply this falsely to the belief that pesticides used in organic farming are safer or superior to those used in conventional farming.

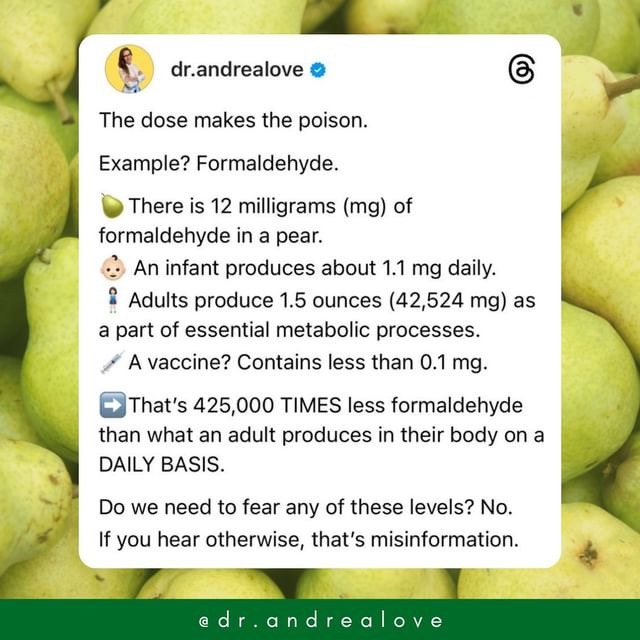

Another common theme in chemophobia is the lack of understanding about dosage and toxicity, discussed here.

The word toxic is meaningless without context.

If you challenge someone about what chemicals they’re concerned about, they might say “well, the toxic ones” - at which point, you might ask them for some examples. Often, you’ll hear common ones: arsenic, lead, other heavy metals, formaldehyde, etc.

Ironically, many of these chemicals that are perceived to be toxic exist in our bodies, and are certainly not “toxic” in that context. Yes, we produce formaldehyde through basic metabolism at levels far higher than what is used to spread fear about ingredients in medications like vaccines.

The dose, route of exposure, and chemical identity dictate the poison.

Chemophobia is impacted by lack of context compounded by low science literacy.

Another major issue is that people do not understand the context in which they have material things.

Do you use a smartphone? That’s because of chemistry.

Do you bake muffins, cakes, pies? That’s because of chemistry.

Do you eat food without getting sick? That’s because of chemistry.

Do we have [relatively stable] food supplies? That’s because of chemistry.

Surgical interventions, medical devices, medications? All because of chemistry.

The inability to factor in context means people can be vulnerable to misleading claims about “toxic chemicals” harming us. And this impacts the development and implementation of new technologies.

For example, when we talk about genetic engineering technology for agriculture, people are wildly misinformed about what that means (see here). This is because they lack the basic science knowledge, yet they consider themselves more informed than they are.

Opponents to GMOs know the least about the topic, yet they think they know the most. They often don’t care what scientists or the data say. As opposition to GMOs increases, objective knowledge of science and genetics decreases, but self-assessed knowledge increased.

In a 2019 study in Nature Human Behavior, 75% of the respondents who scored themselves as “caring a great deal” about GM foods believe they’re harmful and bad for our health. Many of those opposed to GM goods could not correctly answer the question: “does a non-genetically modified tomato have genes?” (spoiler: yes, every organism has genes).

Self-assessed confidence about science means that people might be relying on false information to make decisions: and these decisions impact more than just themselves.

Indeed, 52% of adults consider themselves interested in issues involving science and technology.

But compare that to the 28% of adults that have objective science literacy, and you can see why this disparity is problematic.

The recent “tampon study” is a perfect example of that. Even healthcare providers were mischaracterizing key details of the study, methods, and context.

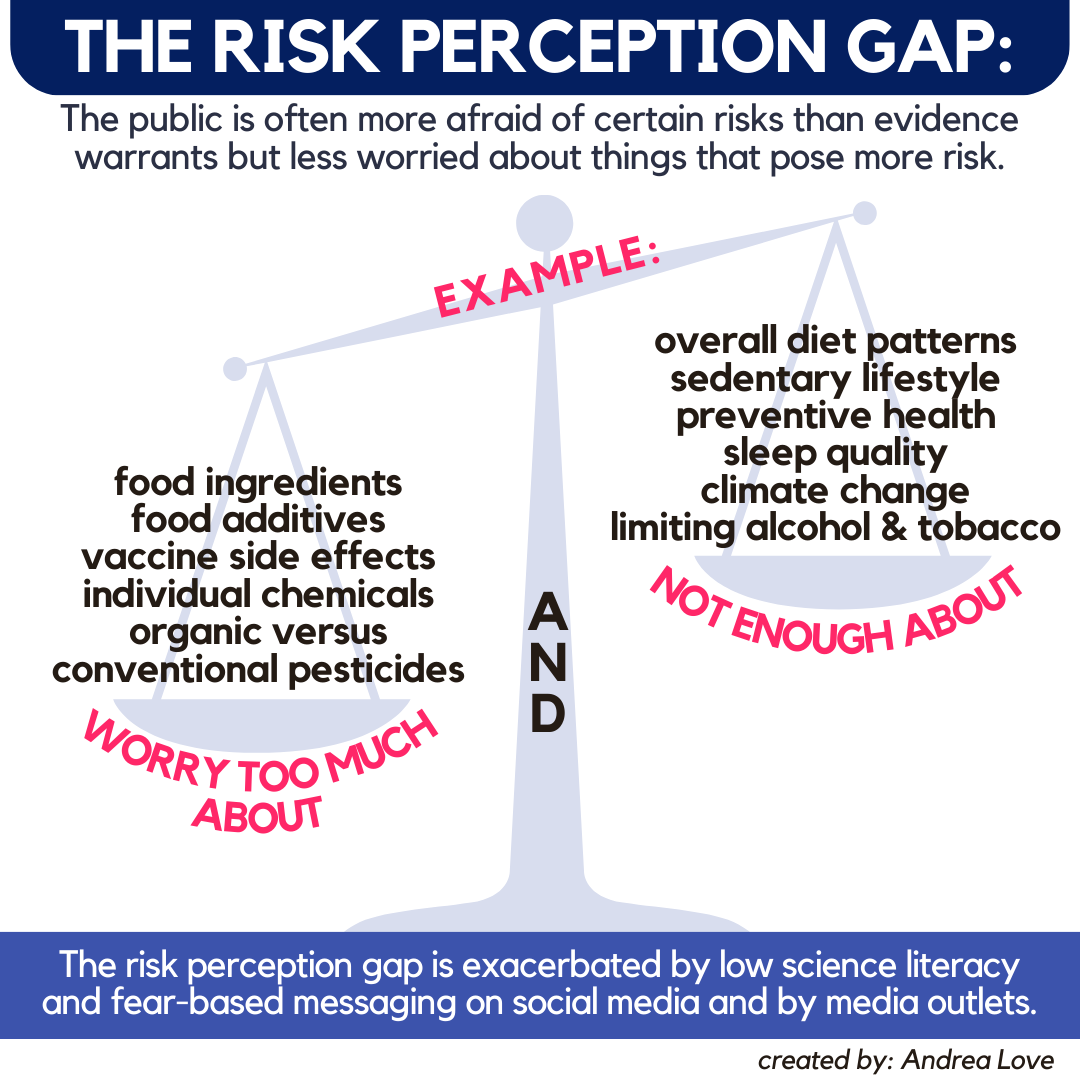

Chemophobia harnesses the risk perception gap.

The risk perception gap is the disparity between real and perceived risks, discussed here. This causes people to fixate on singular chemicals, food additives, vaccine ingredients, but not on things that play a much more impactful role in daily life and health.

You see that also with viral claims about the “harms” of processed foods, without understanding that those terms mean very little scientifically, and the harms are more related to overall lifestyle habits than whether or not you eat a single food.

Ironically, many of those same people spreading fear about tampons, or food ingredients, or preservatives, or pesticides don’t seem to have scrutiny for things that aren’t regulated for safety, like dietary supplements.

Chemophobia impacts policies and laws, and not in a good way.

If a majority of adults are not scientifically literate, that means a majority of voters and government officials are also not scientifically literate. That means outcomes of elections may lead to decisions, policies, and laws that don’t align with factual evidence. When politicians are influenced by their constituents or personal beliefs, they may be more concerned with popularity for reelection or conceding to public opinion than adhering to data.

This has immeasurable harms to our public health and safety and in our ability to develop and implement novel technology. Some examples:

Chemophobia drives opposition to genetic engineering technologies which hinders the development of crops that can withstand more extreme climates, grow in places that were previously inhospitable, produce higher yields with fewer pesticides.

Chemophobia drives anti-vaccine opposition, false claims about ingredients in medications, and erosion of trust in evidence-based science and medicine.

Chemophobia leads to safe ingredients that being banned and demonization of health food items, which can lead people to eliminate nutritious foods from their diet, exacerbating a myriad of health outcomes.

Chemophobia can force companies that develop consumer products like cosmetics, tampons, and skincare to remove safe and effective substances, which can impact everything from raw materials that can be used to the final product. This can mean increased costs, decreased safety, increased ecological impact, and legitimizing misinformation.

People lack context for the domino effect these fears have and the money that funds anti-science rhetoric.

The Environmental Working Group (EWG), authors of the Dirty Dozen list are primarily funded by largescale organic farms. If donors profit, they profit as well.

Even media outlets have a profit motive to share clickbait. Drive traffic to your site? Increased profits.

The anti-vaccine movement has millions of dollars and very powerful people behind it, including the likes of Andrew Wakefield, RFK Jr., and other celebrities.

Science literacy is essential to combat chemophobia.

We need improved science literacy. Unfortunately, most people can’t:

separate fact from fiction

choose experts wisely

draw valid conclusions from the same raw data

understand the full context in which certain studies are performed

follow full data sets rather than components that support pre-existing biases

do their own research

This means most people cannot to make appropriately informed decisions concerning many of the scientific issues facing us today. While that needs to start with our education systems, there are other things that can be done.

Journalists and the media need to be responsible when reporting.

Be educated on scientific evidence and appropriately interpreted results

Make a greater effort to report findings honestly without bias

Avoid clickbait headlines that play into misinformation

Use CREDIBLE and RELEVANT experts to consult on stories

The public needs to stop conflating notoriety and celebrity with expertise.

Scientists and experts can play a part too.

Openly discuss scientific findings, limitations of studies, and the scientific method.

Educate people on facts while acknowledging fears.

Explain scientific concepts in terms that the public can understand

Call out misinformation and correct it

We need infrastructure to do this, though.

Many who spread chemophobia have reach, networks, and money.

Many scientists who combat this do so on their volunteer time, and lack the bandwidth, time, and resources to expand their reach.

Social media companies are not incentivized to combat misinformation.

Chemistry dictates life and chemical science is critical for nearly every topic and problem on our planet, from medical developments, food supply, sustainability issues, climate science, and more. Public fears around chemicals and chemistry can hinder progress and even worsen the state of affairs.

That’s why chemophobia is a global health crisis. We need everyone in society to take an active role in combating this on every level in order to ensure our health and safety and the future of our planet.

Thanks for joining in the fight for science!

Thank you for supporting evidence-based science communication. With outbreaks of preventable diseases, refusal of evidence-based medical interventions, propagation of pseudoscience by prominent public “personalities”, it’s needed now more than ever.

Stay skeptical,

Andrea

“ImmunoLogic” is written by Dr. Andrea Love, PhD - immunologist and microbiologist. She works full-time in life sciences biotech and has had a lifelong passion for closing the science literacy gap and combating pseudoscience and health misinformation as far back as her childhood. This newsletter and her science communication on her social media pages are born from that passion. Feel free to follow on Instagram, Threads, Twitter, and Facebook, or support the newsletter by subscribing below: