10 years ago, my big brother Brian died by suicide.

My fight against science misinformation is personal, because it costs lives like his.

Please note: this piece is more personal than usual, and it may be triggering for others who have lived through similar experiences.

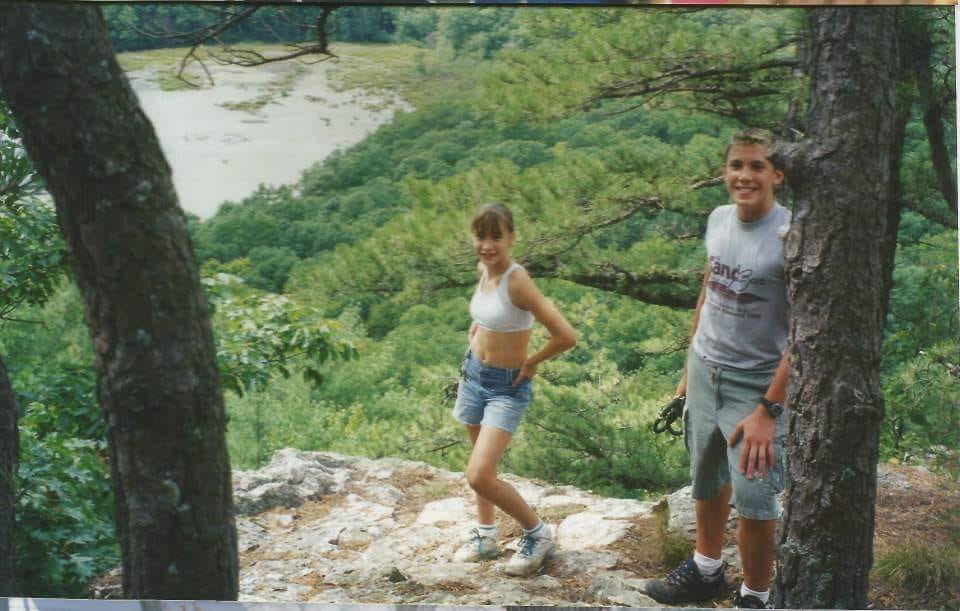

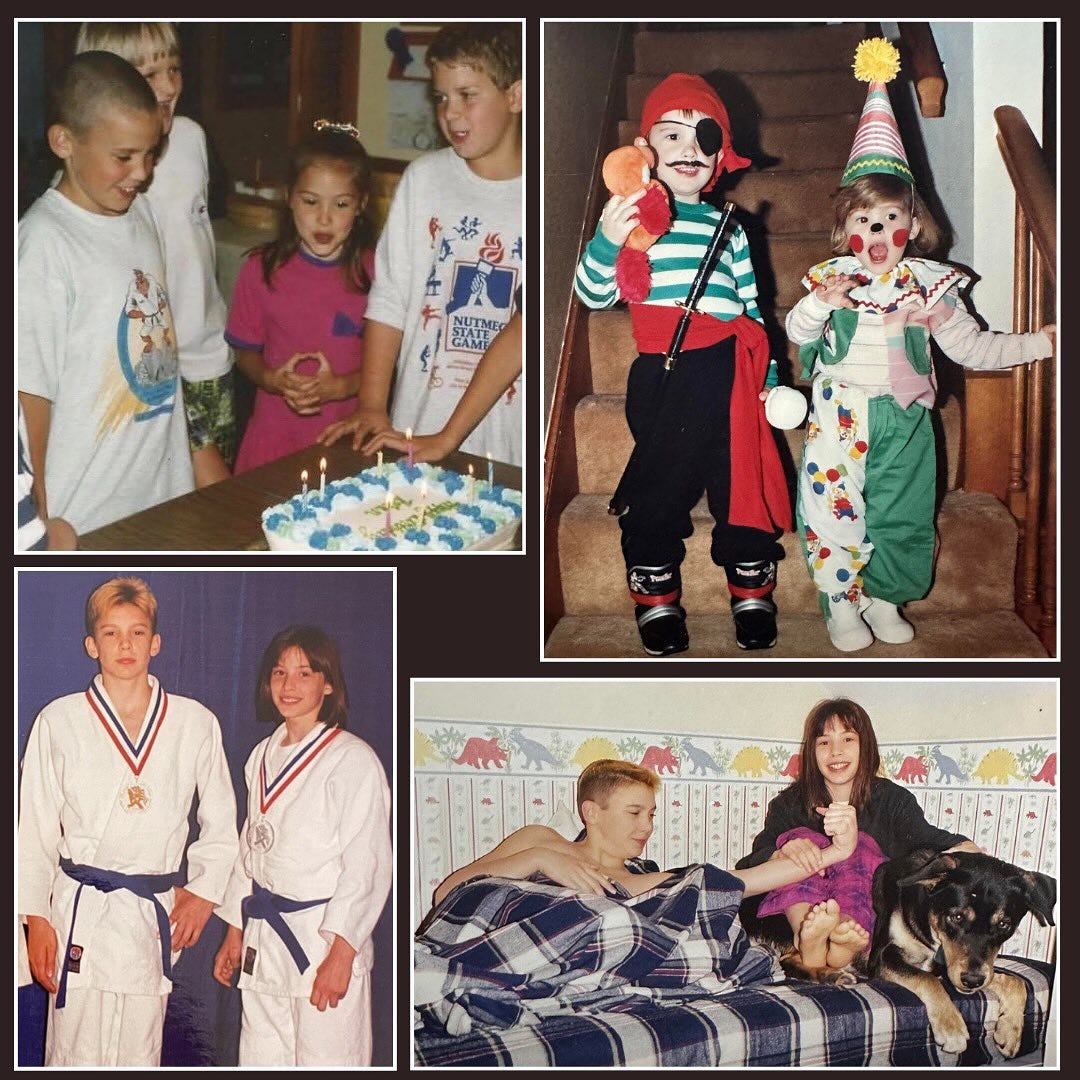

A decade without my big brother, Brian.

A decade living with a piece of me torn out of my body.

A decade of grief, guilt, questions.

I have his suicide note memorized. I read it when the police released his personal effects. It pops into my head when I least expect it. Each time, it destroys me. Those final words—they were the words of someone who wasn’t my brother—and yet, who was.

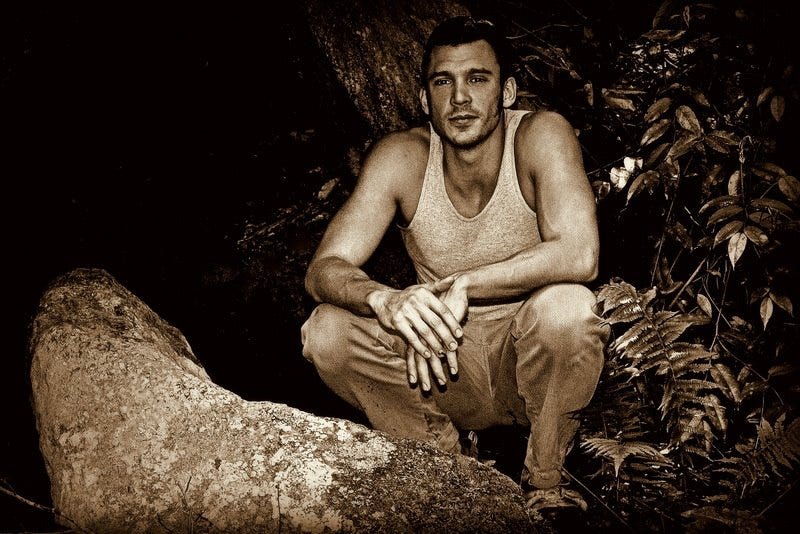

Brian struggled with bipolar disorder for most of his life. People that knew him in passing, during his teenage and young adult years, thought of him as brilliant, charismatic, the center of attention. And he was. But that was also the mania talking. It wasn’t until the last couple of years that the depression side really emerged.

And as someone who also struggles with depression and anxiety, I knew all too well how dark that place could get. And Brian’s depression was darker than most.

I remember that final Christmas. I have the family photos we took. I can’t look at them without crying, because even then, he was a shell of who he used to be.

After he died, my own mental illness was magnified. My anxiety became unmanageable. The grief compounded it all.

Grief isn’t linear. It isn’t something you “get over.” It’s something that fundamentally changes you, forever. I carry it every single day: in my career, in my own mental health challenges, in how I view the world, in my understanding of the bad actors who exploit vulnerable people like Brian, and my actions to combat the harms of misinformation that cause needless suffering.

Our childhood influenced the scientist I became.

Brian and I grew up in Eastern Connecticut, with a house that abutted a wooded park. We spent most of our childhood in the woods: exploring, collecting bugs, flipping rocks to find salamanders, hiking with our dogs. Unlike our friends, we didn’t have video games growing up. We didn’t watch much TV.

We understood the world by exploring it, and thrived on learning as much as we possibly could. Those years were when my scientific mind was born.

Before I pursued my career in biomedical science, Brian and I were asking questions, running “experiments” in nature. He was my first science partner.

Did I get Giardia a few times because I thought nothing of taking a swig from a puddle? Sure.

Did I become mildly obsessed with leeches after finding one attached to me after swimming in Pachaug State Forest pond? Obviously.

Did I insist on telling my entire second grade class detailed information about the lifecycle of a tapeworm because of the assortment of cats and dogs (and axolotls, guinea pigs, hamsters, etc) we had growing up? Absolutely.

But it was worth it—because my fascination with the natural world and the “creepy crawlies” evolved into my career today.

Brian and I were different, but we had the same intense passion.

Brian and I were both intense. That was one our biggest similarities—our passion, our drive, the way we threw ourselves into what fascinated us.

Brian? Maybe a bit on the obsessive side, although I suppose the same could be said about me. He jumped from hobby to hobby. Stamp collecting. Piano. Judo. Fly tying. Fly fishing. Skateboarding. And he would get really good at whatever held his passion for that time. And then off to the next idea.

Our minds were always racing, often not cooperating. We both tried to exist in a world that really wasn’t adapted for our personalities. We were both not part of the popular crowd. Not the affluent kids. Not the team sport kids. Not in band. We did judo before UFC existed. We played piano. We didn’t wear Hollister or Aeropostale or Limited Too. We were nerds, when being a nerd wasn’t cool. (It’s cool, you just have to embrace it).

As we grew up, the ways we channeled our passion changed.

Brian’s intensity became a source of suffering. His bipolar disorder distorted his sense of reality, his thoughts, his feelings. He sought escape, while I sought structure and solutions—the makings of a scientist. While I started to embrace my scientific world, he was drawn to chaos.

Everyone in our hometown could launch into an absurd story about B. Love — stories that you’d think were made up if you didn’t actually know Brian. This was, of course, his mania. But people in passing just saw the outgoing, energetic, charismatic persona he displayed.

Beneath that, we were more similar than people realized. We both needed to understand things. We just went down very different roads to try to accomplish it.

Unfortunately, Brian’s road led him toward self-medication and conspiratorial thinking.

Brian’s need to understand drove him to conspiracy theories, whereas mine drove me to science.

Brian was always questioning things—authority, conventional wisdom, systems that governed the world. In fact, he dropped out of high school 2 weeks before his own graduation, even as he was the Salutatorian for his class. Why? Mental illness with a splash of anti-establishment rhetoric.

His skepticism came from mistrust. Back then, a lot of us thought his actions were to stir up controversy, to make a spectacle. Now, I understand that a lot of it was because he didn’t feel like he fit in this world.

This mindset is common among people with mental illness, especially when they haven’t been able to get the treatment they need and deserve.

Brian self-medicated to try to quiet his mind. He was a frequent flyer on Erowid (anyone else remember that site?) — before he came to realize that he had bipolar disorder in a world that doesn’t understand bipolar disorder.

Brian was brilliant: both a blessing and a curse.

And he had an ego—to be sure. That combination: brilliance, ego, mental illness: led him to conspiracy theories. Many people cling to conspiracy theories because it feeds the ego. Brian believed he was party to secrets that no one wanted him to know.

Did we really land on the moon? Brian would argue the evidence for hours.

Is Area 51 filled with aliens? That was another fascination for him.

If he were alive today, he would have been pulled into wellness pseudoscience, because he always leaned that way.

When he was living in an Ecovillage in Black Mountain, North Carolina, he injured himself with a machete, losing a decent chunk of flesh on his leg. Instead of taking the antibiotics prescribed at the urgent care center, he made a poultice of plant material that he filled the wound with. Suffice it to say, he started the antibiotics 3 days later.

The problem is, the conspiracism made it more difficult for him to get help. Real help. Help that could have (maybe) made a difference. He didn’t trust medical professionals; he knew better than the psychiatrists.

He didn’t want to take prescribed medicines—he’d rather take DMT he made himself or ayahuasca or mescaline or psilocybin—things which certainly exacerbated his mental illness and likely contributed to symptoms during his teenage years.

Mental illness lies to people.

Brian’s mental illness lied to him until the very end. And that breaks my heart most of all. I have felt this way too, with my own mental illness. I also have survivor’s guilt—did I abdicate my responsibility to do more to help Brian because I was so wrapped up in finishing my PhD at the time?

Mental illness convinces you that you are a burden. That you are broken. That you can’t be helped. Or that you don’t deserve to be helped.

It isolates you. It erodes your will to survive when you already live with a brain that is working against you.

And for many people, that can be overwhelming. More than overwhelming, in Brian’s case. Insurmountable.

And that’s what’s so harmful about people like RFK Jr who lie about mental health and treatments

People often don’t realize that there are reasons why I get so angry about science and health disinformation—or people like RFK Jr.

It’s because I understand the dangers as both a scientist AND a human being.

RFK Jr. has spent years pushing dangerous lies about mental health (and he makes money off these lies too).

He claims that psychiatric medications cause mass shootings. He claims that ADHD and autism are the result of toxins, food dyes, vaccines. He lies to people, suggesting that antidepressants are a “Big Pharma” conspiracy rather than life-saving treatments for millions.

He convinces people with REAL medical issues that they are being lied to. He is the one lying.

He has said recently that people are addicted to ADHD and antidepressant medicines and it’s a “threat” he is going to tackle as HHS Secretary by sending people to “wellness farms.”

As someone who was also recently diagnosed with ADHD (I 100% have had it my entire life), medication has been a literal life-saver.

He has even suggested that he wants to interfere with the FDA and approvals of psychiatric medicines. Let me be very clear:

Mental illness is real. It is a chronic disease. It is insidious, serious, and fatal.

RFK Jr.’s lies will cause needless pain and suffering. It will cause more deaths among people like Brian. And it definitely won’t tackle the chronic disease “epidemic” that he claims to care about.

These lies about mental illness cause people who are already struggling to question whether they deserve help. It fuels the already overwhelming stigma of mental illness, which means people delay or avoid treatment until it might be too late.

It makes them feel weak if they do seek treatment.

It causes people who are suffering to further isolate themselves, increasing their vulnerability to potential fatal consequences.

All of this happened with Brian.

And people like RFK Jr. ensure it will happen to others, too. This isn’t abstract to me. It’s personal.

When you tell people that psychiatric medicine and therapy is a scam, you push them further from life-saving help.

When you tell people that their suffering isn’t neurobiology but a toxin they can detox from, you convince them to waste time and money on fake treatments, delaying real interventions.

When you tell people the world is lying to them, you isolate them—one of the most dangerous things when you have mental illness.

Brian didn’t just struggle with bipolar disorder. He struggled with living in a world that didn’t have space for people with mental illness. He needed more support than our society could provide. A society where mental illness is challenging enough to manage without adding to the skepticism he had embraced.

Brian didn’t get the time he needed to climb out of the darkness. But others can. That’s why I will never stop fighting disinformation that pulls people away from real care and real help.

Mental illness is not a conspiracy. It is not a choice. It is not something you can will away with positive thinking. Or just going out for a run. I run marathons. I still have mental illness.

Mental illness is real. It’s painful. And it’s a chronic illness that people can live with—but not if misinformation becomes public discourse.

I miss Brian every single day. Some days, even ten years later, it hits me like a ton of bricks. And as different as we were, I carry the words he wrote to me, as a reminder:

We are still more similar.

I’ve thought a lot about this message from Brian. I’ve had years of conversations. Why, if we are so similar (and we are) did Brian succumb to his illness and I am still here? My psychiatrist phrased it in this way:

You were able to turn your passion into something constructive. Brian wasn’t.

I am here because I sought resources and treatment. I understood that stigma shouldn’t stop medical care.

I am here because science is not just my career—I understand that it is not the enemy. It gives us knowledge and answers. Science saves lives.

I wish Brian had these tools. More than anything, I wish he were still here.

I wish that the people spreading misinformation about mental health would realize that their words have consequences. Those consequences can be deadly. This is not hyperbole, it’s reality. And I owe it to Brian to keep calling it out.

Love you, B. Always and forever.

This newsletter is free, but it’s able to sustain itself from support I receive from a small percentage of regular readers. If you value science-based information, consider upgrading to a paid subscription:

Now, more than ever, we all must join in the fight for science.

Thank you for supporting evidence-based science communication. With outbreaks of preventable diseases, refusal of evidence-based medical interventions, propagation of pseudoscience by prominent public “personalities”, it’s needed now more than ever.

More science education, less disinformation.

- Andrea

ImmunoLogic is written by Dr. Andrea Love, PhD - immunologist and microbiologist. She works full-time in life sciences biotech and has had a lifelong passion for closing the science literacy gap and combating pseudoscience and health misinformation as far back as her childhood. This newsletter and her science communication on her social media pages are born from that passion. Follow on Instagram, Threads, Twitter, and Facebook.

Andrea, this is so stunningly poignant and beautiful. Much love to you. Thank you for sharing a tiny part of your brother’s story, and yours with him. As a dietitian, I certainly get irritated by nutrition misinformation, but as someone with mental illness, I get red-faced infuriated by mental health misinformation. You already know how deeply I appreciate you. Your work is a gift. Keep fighting.

Andrea, thank you for sharing this. This is a profound message on so many different levels. It also gives a lot of context to your very obvious passion in everything that you do.